October 28, 2009

The cable period drama Mad Men attempts to answer the question: What would have Cary Grant’s stylish advertising executive in Hitchcock’s 1959 barnburner North by Northwest gotten up to if”instead of getting chased by spies all the way to Abraham Lincoln’s nose on Mt. Rushmore”he and his superb suits had simply stayed on Madison Avenue during the advertising industry’s storied golden age?

After the Tom Cruise generation of boyish, small, and energetic stars, it’s refreshing to see a Golden Age of Hollywoodish leading man like tall, dark, and handsome Jon Hamm, who plays creative director Don Draper as the strong, silent type. Granted, the concept of a reticent copywriter doesn”t make much sense, but the show has become a huge hit with media folks, more than a few of whom are married to people in the ad business.

Mad Men is the latest of this decade’s extended plotline dramas to rivet the attention of the higher end of the TV-viewing audience.

We constantly hear that long-form TV dramas are better than ever. That’s probably true, but few of today’s fans can remember how quickly we all tend to forget past serial dramas that once seemed indelibly memorable.

In contrast to serial shows like Mad Men, Lost, and 24, most television sit-coms and some dramas “reset” at the end of each episode: no matter what zany antics transpired during tonight’s episode, Homer Simpson will be right back at the nuclear power plant next week, unchanged except for the vaguest of memories.

An increasing number of prime-time dramas, however, tease audience interest by ramifying a single complicated plot over the life of the show. By not reaching a conclusion, they leave audiences asking each week, “And then what happens?” This gives fans plenty to chew over with each other until the next episode. (Here, for example, is Slate’s 59-part [!] discussion of the current third season of Mad Men.)

Fans like to call serials “novelistic” (although the unkind term “soap operaish” can also be apt).

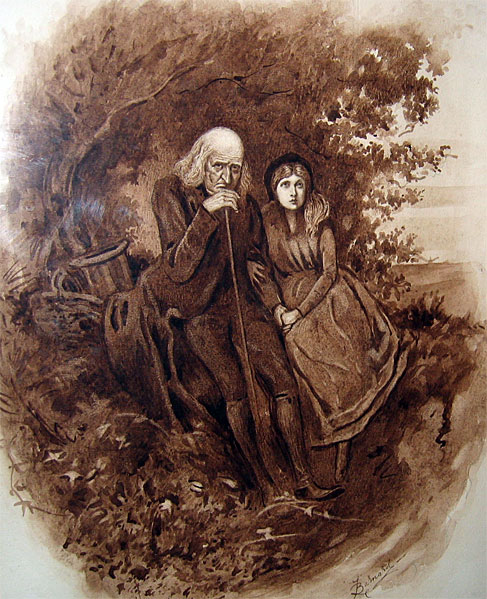

Novelists have given up publishing their works in installments, even though that was hugely profitable for numerous 19th Century novelists, such as Charles Dickens. His books were typically serialized in 20 monthly installments of 32 pages of text and 16 pages of advertising. The protracted death of Little Nell in Dickens” serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop

Novelists have given up publishing their works in installments, even though that was hugely profitable for numerous 19th Century novelists, such as Charles Dickens. His books were typically serialized in 20 monthly installments of 32 pages of text and 16 pages of advertising. The protracted death of Little Nell in Dickens” serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop turned into an ongoing international tragedy. At New York’s piers in 1841, American fans would shout out to docking boats from England, “Is Little Nell alive?”

Tom Wolfe, who had long denounced 20th-century literary fiction for not showing us The Way We Live Now (an Anthony Trollope novel that was, of course, serialized), published his first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities

, in 27 installments in Rolling Stone in 1984-1985. Jan Wenner paid him $200,000 for the rights, and the pressure forced the vastly ambitious Wolfe past the writer’s block he had developed after spending years hinting broadly that one of these days he was going to show all living novelists how fiction should be written.

Unfortunately, Bonfire didn”t make much of a splash in Rolling Stone … because it wasn”t very good. It was a first draft, and Wolfe’s first drafts turned out not to be as good as Dickens’s had been. Moreover, there are obvious problems inherent in going public with the beginning before you”ve written the ending. (This has been a particular conundrum for American TV serial dramas because the writers don”t even know how many years the show will run. Thus, they tend to start strong and peter out. In Britain, however, fixed durations serials are more common.)

<iframe src=“http://rcm.amazon.com/e/cm?lt1=_blank&bc1=000000&IS2=1&bg1=FFFFFF&fc1=000000&lc1=0000FF&t=taksmag-20&o=1&p=8&l=as1&m=amazon&f=ifr&md=10FE9736YVPPT7A0FBG2&asins=0312427573” style=“FLOAT: right; MARGIN: 10px 10px 10px 10px; WIDTH: 120px; CURSOR: hand; HEIGHT: 240px” alt=”“></iframe>

Wolfe then rewrote Bonfire after doing the additional research necessary to change his protagonist’s career from Wolfe’s lazy initial choice”writer”to a much more timely and under-publicized one”bond-trader. Revised, Bonfire became a huge bestseller. A long string of subsequent real-life incidents all the way up through the Duke lacrosse rape hoax that seem like plot twists out of Wolfe’s tale of the hunt for “the Great White Defendant” has cemented its status as the Great American Novel of the 1980s.

Movies remain a troublesome format for Dickensian storytellers. Adapting big novels to fit within the limited length of a film remains difficult. Even at 238 minutes, Gone With The Wind‘s screenplay had to be a miracle of concision. The 125-minute Brian De Palma version of Bonfire of the Vanities was a notorious flop.

With 1967’s Forsyte Saga (a 26-episode adaptation of five books by Nobel laureate John Galsworthy) and 1971’s Upstairs, Downstairs, the Brits pioneered high-class soap operas that galvanized audiences by artfully following an ensemble of characters through intersecting nested plots in a carefully detailed time and place.

The American equivalent came along in 1987, Edward Zwick and Marshall Herkovitz’s thirtysomething, which artfully portrayed an ensemble of old college friends centered around a yuppie advertising man, Michael Steadman, an undersexed Don Draper for the feminist era.

In its time, thirtysomething was probably the best written and certainly the most realistic show on television (my twentysomething new bride and I watched it wide-eyed as we learned what was in store for us). For a few years, it had a limited but lucrative yupscale demographic enthralled over whether Michael and Hope would be able to make their marriage work and other questions that seemed a lot more interesting at the time than they do now. (At this point, I can mostly just remember Miles Drentell, the ruthless Sun Tzu-quoting CEO of the trendy ad agency where Michael worked.)

In its time, thirtysomething was probably the best written and certainly the most realistic show on television (my twentysomething new bride and I watched it wide-eyed as we learned what was in store for us). For a few years, it had a limited but lucrative yupscale demographic enthralled over whether Michael and Hope would be able to make their marriage work and other questions that seemed a lot more interesting at the time than they do now. (At this point, I can mostly just remember Miles Drentell, the ruthless Sun Tzu-quoting CEO of the trendy ad agency where Michael worked.)

The downside of “And then what happens?” is that the answer usually turns out to be “A whole bunch of stuff.” While satisfying at the time, serials tend to be consumable only once. For example, although thirtysomething was immediately influential within the entertainment industry, it was almost forgotten by the public once its run was over in 1991. (It wasn”t even released on DVD until this year).

On the other hand, Seinfeld (something of a comic version of thirtysomething, but also a classic reset show in which not even, say, the sudden death of a fiancé has any discernible emotional impact on a character) remains a money machine in syndication.

Another chronic problem with shows that don”t reset is creeping soap operaization. Female fascination with relationships tends to crowd out every other subject over time. Even House, with the wonderful Hugh Laurie as a Sherlock Holmes-like genius/misanthrope solving one medical mystery per week, has become more of a soap opera over the years.

Similarly, Mad Men underexploits its setting in the advertising industry, always a fun business to portray, in favor of emphasizing relationships. In the pilot episode set in 1960, for instance, Don Draper is proclaimed a genius by his clients and colleagues for dreaming up a new slogan for Lucky Strike cigarettes: “It’s Toasted.” In reality, a lame phrase like that would have been laughed at in 1960. Lucky Strike’s “It’s Toasted” slogan actually dates to 1917.

Of course, the advertising business isn”t really what Mad Men is about.

Of course, the advertising business isn”t really what Mad Men is about.

So, what do I think the show is about?

Well, in the spirit of today’s serials, you”ll just have to wait until next Wednesday to find out.

I will mention one thing: the show relentlessly exposes the sexism of pre-feminism men like Don Draper, seemingly for today’s women to cluck over. Instead, they gasp and squeal. Why?

Because women find sexism sexy.