December 02, 2020

Source: Bigstock

When reviewing movies, I’m less interested in propounding whether or not a film is, in my opinion, good than in explaining which types of people would find this a good film. As an old market researcher, it is only natural for me to pay attention to who would like what, which makes me less arrogant about my own tastes than most critics.

My old friend Paleo Retiree comments:

One thing that makes Steve’s pieces about books and movies valuable and enjoyable is the way he de-emphasizes the opinion-and-reaction dimension of reviewing and foregrounds instead reflections, issues, observations and information. He’s genuinely interested in other people and the larger world, and he wants to give readers material that other reviewers aren’t coming through with. Value added!

Thus, I couldn’t resist downloading the data behind a new research paper by marketing psychologists Gideon Nave, Jason Rentfrow, and Sudeep Bhatia entitled “We Are What We Watch: Movie Plots Predict the Personalities of Those who ‘Like’ Them.”

From a large sample of Facebook users who made public their results on a standard personality test, the authors scraped which movies the test-takers chose to “like” on Facebook. They found 846 films that had been liked by at least 250 people who had taken the psychology quiz, ranging in date from Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz in 1939 up through 2011. For each film, they constructed an Aggregate Fan Personality Profile (AFPP).

The participants are mainstream Americans rather than cinephiles, unlike with the Internet Movie Database’s ratings. The most often liked movies in this female-majority Facebook archive are the Twilight movies, followed by Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and The Hangover (the film most frequently cited by men). While IMDb’s ratings are dominated by male tastes (for example, IMDb’s No. 1 is the prison movie The Shawshank Redemption, which features almost no speaking roles for women, followed by the first two Godfather movies), the majority of the Facebook participants are women, typically averaging in their 20s.

Each participant has a personality profile based on the currently dominant Five Factor or OCEAN model, which posits five main dimensions of personality:

(1) Openness to experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious)

(2) Conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. extravagant/careless)

(3) Extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved)

(4) Agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. challenging/callous)

(5) Neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. resilient/confident)

Why five axes rather than, say, four or six? Well, five has been the most popular consensus figure among empirical research psychologists since the 1980s, a reasonable trade-off between the contrasting advantages and disadvantages of lumping a model of personality into fewer dimensions or splitting it into more. But this isn’t carved into stone: Fifty years from now psych majors might be taught a three-factor or a seven-factor model.

The OCEAN analysis was worked out largely by having college students fill in endless personality quizzes and then applying the art of factor analysis to the results. It’s uncertain if it works as well outside of the WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) world. But it serves adequately for American movie fans on Facebook.

To show you how, let’s compare who likes a couple of quite different famous movies: Pretty Woman with Julia Roberts versus Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

First, there’s a big difference in sex: 92 percent of the 2,409 people who like Pretty Woman are women, compared with 24 percent of the 538 who like 2001.

The average age of Pretty Woman supporters is 28, not much different than the 26 for 2001.

Not surprisingly for a film that attempted to depict just how alien an alien intelligence might be, 2001 fans rank very high in Openness, 11th out of the 846 movies. The only famous film that scores higher is David Lynch’s dream-surrealist Mulholland Drive. In contrast, Pretty Woman enthusiasts fall at only the 12th percentile out of the 846 films on Openness. They tend to be rather basic.

Openness correlates with aesthetic interests, so the films at the top tend to be spectacular-looking: I can recall seeing 2001 at the Cinerama Dome in 1968 when I was 9 and being sure I had never been to a movie that looked like it before (and maybe nobody else had either). Pretty Woman, on the other hand, was directed by sitcom writer Garry Marshall, an efficient helmsman but not one to pioneer lens flare as an art form.

In general, the median movie is liked by a set of fans who average a quarter of a standard deviation higher on Openness than the general public. Movies are a cheap way to see the world and to put yourself into other people’s shoes.

But on Conscientiousness, Pretty Woman’s fan base scores at the 97th percentile versus 26th for 2001’s.

The Julia Roberts film’s admirers come in at the 81st percentile in Extraversion, while 2001’s are as introverted as the stereotype about science-fiction buffs implies: They fall at the 2nd percentile.

Not surprisingly, Pretty Woman’s audience is fairly Agreeable (75th percentile), while devotees of the intentionally inhuman 2001 are not (15th percentile).

Finally, both groups are above average in Neuroticism.

In other words, the stats vindicate the stereotypes: People who like Pretty Woman on Facebook are more or less Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion come to life, and the typical 2001 nut is Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons.

In general, women are less chauvinistic than men about movies. Among the top 10 pictures for highest percentage of male fans, famous ones include Oliver Stone’s Platoon, Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down, Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, and two Kubricks: 2001 and Dr. Strangelove. But women still furnish 22 to 25 percent of these guy films’ likes.

In contrast, 67 of the 846 movies had endorsers who were no more than 10 percent male. Granted, most of these female-friendly films are less distinguished than 2001. Still, Sense and Sensibility, which Emma Thompson adapted from the Jane Austen novel and starred in, is terrific. But only 4 percent of its fans are men.

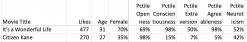

We can use this database to compare less dissimilar movies as well. Consider two 1940s masterpieces: Orson Welles’ liberal Citizen Kane and Frank Capra’s conservative It’s a Wonderful Life.

The visually innovative Citizen Kane wins on Openness, of course.

In contrast, It’s a Wonderful Life is a proto–Twilight Zone fable about a good man, George Bailey, with a hunger for Openness, a desire to see the wide world. But a malevolent fate seems determined to keep him from ever setting foot out of Bedford Falls, constantly drumming up new small-town crises that only his conscientious presence can resolve for the good of the community. Hence, Capra’s movie scores at the 98th percentile on both Conscientiousness and Agreeableness.

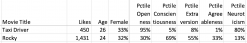

Rocky beat out Taxi Driver for the 1976 Best Picture Oscar at the peak of the 1970s Italian-American movie boom.

Rocky fans are about three times as numerous as fans of Martin Scorsese’s disturbing film. Both audiences are two-thirds male.

Admirers of Travis Bickle, such as John Hinckley Jr. (who was inspired by the De Niro character to shoot Ronald Reagan in the hopes of winning the heart of Jodie Foster), tend to be weirder than advocates of Rocky Balboa, as shown by Taxi Driver coming in at the 95th percentile and Rocky at the 30th on Openness.

Rocky’s fans aren’t quite as Conscientious as their hero (69th percentile), but they beat Travis’ fans (5th percentile) by a mile.

Taxi Driver addicts also rank low in Extraversion (8th percentile) and, especially, Agreeableness (1st percentile): “Are you talking to me?”

They are, though, much more Neurotic (80th percentile) than are sunny Stallone followers (13th percentile).

One finding of the authors is that fans of sports movies, such as Rocky, are the single most distinctive genre in terms of personality traits:

Surprisingly, the genre most strongly associated with all AFPP dimensions is sports, whose fans are lower on Openness and Neuroticism, and higher on Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Agreeableness.

In other words, people who like movies about sports tend to rank high on the sociable personality traits and lower on the more artistically related traits.

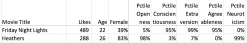

For example, the two movies with the most extreme personality profiles are the polar-opposite high school cult classics Heathers, in which Wynona Rider is conflicted over whether or not to finish murdering all the popular girls, and Friday Night Lights, about a blue-collar Texas football team trying to win the state title.

Sports movies rank high in Extraversion, along with fraternity movies such as Old School and black movies such as Friday. At the other end of the scale, the films that appeal most to introverts are largely Japanese anime such as Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away.

Winona Ryder movies are strong in Neuroticism, with the most neurotic movie of the 846 being her hot-chicks-in-a-mental-institution Girl, Interrupted with Angelina Jolie.

The least neurotic movies beside Friday Night Lights include Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible, Boyz n the Hood, and Stephen Hunter’s Shooter with Mark Wahlberg as expert Marine trigger-puller Bob Lee Swagger.

What’s true of sports movies is likely true of sports in general: Athletes tend to be better team players than are artists.

This may help explain the mystery of why Harvard puts such a heavy thumb on the undergraduate admissions scale to help applicants who are fine athletes: Jocks are likely to get better jobs, to rise higher in management, and, in the fullness of time, to write much bigger checks to their alma mater’s development office.

It’s almost as if the nation’s more conservative personalities could have more influence over liberal institutions than they currently exercise.