August 11, 2013

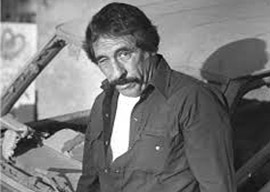

Pablo Acosta

As the profits climbed, so did the legal heat. Pablo kept the supply high in spite of busts such as one instance in Alamogordo, New Mexico, where police pulled over and deconstructed a faulty truck to find it carrying 286 pounds of cocaine. It was only one truck of many whose merchandise that day carried an estimated street value of $50 million. In maintaining his business, Pablo was not above using force, though the violence is not comparable to that of today’s narcos.

No evidence I have seen after years of research into this story”with the help of his biographer, investigative journalist Terrence Poppa (who lives in seclusion for fear of incidental reprisals from a cartel)”indicates sadism on Pablo’s part.

For example, when he correctly surmised that he was under special investigation by the FBI, Pablo had the suspected informant captured while driving south of the border via Juarez. As the informant, nicknamed Gene “the Bean,” cruised off the freeway and onto the Chihuahua highway”a lonely stretch of road and mostly deserted because of its length”he found himself heading straight for a dragnet of three pick-up trucks blocking the highway both ways. Pablo and his lieutenants were waiting for him there. Such was Pablo’s spell that Gene pulled to a stop and surrendered immediately. The lieutenants forced Gene into one of their trucks and sat him at the steering wheel. Pablo got in beside him and shut the door. It was only the two of them in the truck. Pablo tied a bandana around Gene’s head, blinding his sight. He put a gun to his head and told him to drive and keep the wheel straight.

Pablo jammed the Magnum hard into Gene’s ear and told him to accelerate faster and faster. As the truck hurtled down the highway”passing 100MPH, 120, 140″Pablo yelled questions at Gene. Was he a rat? Did he know about Alamogordo? Why should Pablo believe anything he said? Gene was sweating, convinced he was meeting his own end”and Pablo’s, too?

The fear wasn”t a problem for Pablo, who would never have become the Acosta of legend had he ever feared for his own life. Forcing a blinded man to drive 160MPH on a narrow highway while risking death at his own hands was an excellent pressure creator and lie detector. It turned out that Gene was a rat, but he was not Pablo’s informant. He told Pablo exactly whom he was informing upon. Pablo eventually used this to his own end down the line and spared the Bean any harm. He was a man of honor in strange ways and when he in no way needed to be.

Then again, as the feds ramped up the investigation and Pablo’s Plaza came under scrutiny, paranoia was kicking down the doors in Pablo’s mind, just as his drug tolerance peaked and plateaued. Finding it harder than ever to stay high, Pablo resorted to Russian roulette so often during drinking sessions that his best men became terrorized by the paranoia.

Acosta was a leader and a strategist. When he made the top of the Most Wanted list near the end of his career, it was clear to him that there was no way out. He had stomach cancer by now, his mind was frayed, and he had the wisdom to see that even the most loyal and highly compensated of his lieutenants were growing out of their roles. He had owned the Plaza for ten years. There was only one way to go from there: down.

Pablo attempted an extraordinary maneuver. When the aforementioned investigator took a personal risk for the sake of landing a great story and naively requested an interview with Acosta, he was granted his wish of a face-to-face meeting with the legend himself.

Why would the most wanted man in North America agree to an interview with a bright young reporter who had become enthralled by Pablo’s legend after hearing endless tales of the kingpin’s generosity to the poor, the wretched, to families wishing to go on holiday, and even to federal soldiers who felt underpaid compared to Pablo’s men? Almost every person on the Plaza was on Pablo’s payroll, children included. Acosta was an authentic Robin Hood, a businessman who gave back to society in a big way and also in small and touching ways. Every week he personally visited a shy thirteen-year old girl and her mother, who cared for her daughter after she mistakenly poured hydrochloric acid onto her eyes thinking the unlabeled plastic bottle was washing water. (There was no running water here.) Acosta supported a region that the government in Mexico City had long forgotten.

Acosta developed a strategy when he understood there was no exit available for him and the US wanted his head at any cost, as he had become the face of the Drug War. The US authorities were not going to let him get away and so be seen to be losing the Drug War. He would beat them to it. And so he did.

The scoop was splashed across the front pages of the El Paso Herald-Post“an intimate and frank discussion of the Drug War from the lips of its greatest warrior at the time. In so doing, Pablo effectively gave himself up. The strategy behind it was as well engineered as one of Pablo’s smuggler trucks. By outing, identifying, and locating himself, he made a high-risk chess move. Announcing it via the press, Pablo offered to give himself up peacefully to the US and the Mexican authorities (who had now created a task force dedicated to taking him down) to help them better understand the insoluble paradoxes of the Drug War and have them see reality the way the very poor see it.

A young man growing up with no education, no local future, and no money in a backwater town such as Ojinaga had two options as he came of age. One, he could join the army and make a living if they would have him. This would work for one in ten youths. Two, he could work for Acosta or any of the thousands of smaller drug-smuggling groups and make a great living shipping contraband to the hungry market north of the border.

Option one would inevitably include providing direct assistance to the drug traffickers, as at the airport, or providing indirect assistance to the trade by manipulating the product’s scarcity value so that the fat cats in government and working for the cartels can line their pockets. It wasn”t much of a choice.

Acosta’s renunciation offer extended to providing the US with the full details of his many competitors and enemies in exchange for a safe retirement. The authorities considered the offer farcical. In any case, they simply needed Acosta’s head as a trophy to pretend they were winning the Drug War. It’s necessary to appear to be winning for the sake of continuing the war. Continuing the war is paramount. It’s the best game in town. It’s floating a lot of boats and a lot of jet skis. It’s even floating Wells Fargo. Decriminalizing narcotics is bad for the participants, even though it’s good for the broader economy. Trade barriers make money.

On the evening they went in to kill him, Pablo had returned from his stroll to the adobe hut where he lived. He dismissed his men early that evening with a little more affection than usual. He didn”t want them to get caught in the crossfire. It was as if he could smell the attack. As if he could hear them preparing beyond the cliffs of the Big Bend National Park. As if he could read the forest and canyons across the Rio Grande, as his father and grandfather and great grandfather”all smugglers”could read signals from the trees made by fragments of mirrors off which the sun would bounce, sending a message to town as was the custom when smuggling a hundred years ago. The days of getting high and lassoing calves for fun, of doing lines off the barrel of an AK-47, of discharging the guns of all their bullets just for fun and crackling the sky like fireworks, those days”twenty years ago”seemed like a hundred years ago now.

The people of Ojinaga were holding an impromptu fiesta in honor of el jefe that evening. Before closing his door on the village that had been hiding him for months, he paused to watch a young boy shoot a clean hoop on a makeshift basketball court whose red soil floor was drying from a rare rainstorm.

When they came, it sounded like thunder. The noise of the Bell helicopters shook the village elders to the core as they saw these USAF machines that might as well have been spaceships, the country people having never seen a helicopter in their lives, let alone on their crop fields.

In the end the Americans didn”t stop and wait for the Mexican backup as was the plan. They simply flew in, disgorged, and let the gunfire rip on the little adobe hut where Pablo had been born and now inhabited as he waited for fate to knock on the door and tell him it was over. In the end, ten thousand and one cartridges told him, razing his house to a ruin in a matter of minutes.

After the last echo of the last bullet had bounced off the last canyon wall, the soldiers approached the little house almost gingerly compared with their demeanor minutes before. Through the smoke and flames, a more curious soldier tries to get a better view through the chaos. He sees a bed. A shape on top. Someone is lying propped up against the wall.

It’s Pablo. In one hand he holds an automatic rifle, in the other a pistol. His eyes are half-open but he does not move. If only we could preserve him like this forever. When his injuries, or maybe the smoke, became too much, he must have lied down on the bed.

The smoke clears some more. Lying beside him on the bed”under his arm, well protected”is the stray dog. The dog, amazingly, is alive. Pablo’s dead. But he looks like he’s ready to shoot anyone who comes through the door.

I”ll leave you with that image, El Gato. And in the words of James Ellroy: “Here’s to the bad men.”

“Bombay