July 06, 2016

Sanford Koufax

The Brooklyn Dodgers had moved to Los Angeles in 1958, the central event in a long cultural war among Jews in the media industries over whether to stay back east or to head west (a conflict amusingly articulated in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall). The entertainment businesses, such as music, tended to go, while the news media stayed. The 1963 World Series, in which the Los Angeles Dodgers, behind the 25″5 Koufax, swept the long-dominant New York Yankees, was seen as a passing of the torch.

In Los Angeles, Koufax and Drysdale became baseball’s Paul Newman and Robert Redford. (Indeed, Drysdale and Redford had been classmates at Van Nuys H.S.) The two Dodger pitchers, the Jew from New York and the gentile from Los Angeles, made a nice pair, symbolic of American pluralism.

Fans liked that Koufax and Drysdale were friends and held out together in spring 1966, forming their own cartel against Dodgers owner Walter O”Malley. The two signed movie contracts with Paramount to give credence to their threat to sit out a year during this era when owners held all the cards. Drysdale and Koufax even agreed to appear on the TV variety show Hollywood Palace:

“Don is expected to sing with his own guitar accompaniment,” a show spokesman told The Times. “Koufax will concentrate on humor.”

Fortunately, Dodger management crumbled under this dire warning, raising Koufax’s pay from $85,000 to $125,000 and Drysdale’s from $80,000 to $110,000. In contrast, Kershaw will earn $34,571,429 in 2016. (Although it may look as if I”m just typing randomly, I”m not making that number up.)

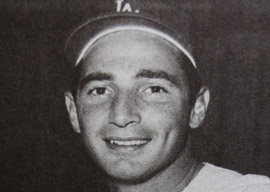

Even though Koufax’s background was stereotypically Jewish-American (he was Brooklyn-born and Long Island-raised), he was also movie-star glamorous in a not typically Jewish manner: tall, handsome, athletic, strong and silent, like John Wayne or Gary Cooper.

He triumphed through physical superiority, courage, and suffering rather than through being brighter than his opponents. I can”t recall a single anecdote of Koufax outsmarting anyone on the field. That wasn”t his style. For Dodger lefties with baseball brains, I”d pick Fernando Valenzuela, who won a Cy Young at 20, long before Koufax reached his prime.

Koufax has spent much of his retirement living in obscure, small towns. Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi explained in 1967 that Koufax had walked away because:

Sandy is a doer; he likes to play golf, to wire up fancy stereo sets, to fool with his cars and to go out and play and have fun, and every time he wound up and threw a baseball he ran the risk that some time in the future, some day maybe 10 years off, he would lose the use of that bad arm and not be capable of doing the things that he wanted to.

In contrast to Koufax, the ambitious Drysdale was a mean son of a gun notorious for knocking down hitters, such as Frank Robinson, who crowded the plate.

Don also starred in a memorable commercial in which the San Francisco Giants manager accuses him of throwing an illegal greaseball, only to have Drysdale triumphantly display to the cheering crowd his bottle of Vitalis nongreasy hair tonic. (Where there’s smoke, there’s fire: Drysdale admitted in his autobiography to throwing the banned spitball.)

Baseball analysts have enjoyed debunking Koufax’s spectacular statistics as a product of his time and place”Dodger Stadium’s huge playing field and high mound, the league’s expansion-depleted talent, and the briefly bloated strike zone.

And yet…Koufax was likely the greatest close-game pitcher ever. Bill James calculated that in 1963″64 Drysdale won the games he should have, but Koufax also won the games in which the Dodgers didn”t provide much offensive support. For example, the Dodgers got only one hit the night of Koufax’s perfect game. James wrote:

Think about it. Given one, two or three runs to work with, Koufax was 18″4. That’s an unbelievable accomplishment.

So Drysdale couldn”t match that. Well, who could?

A commenter at Joe Posnanski’s site who calls himself Moeball wrote that he had looked up famous pitchers” best half decades, and none ever won half of his games in which his team had provided him with two runs or less…

Except for Sandy Koufax. From 1962″1966 he went 27″24 when given 2 runs or less of support. He’s the only regular starting pitcher in history to be able to do this. He’s the only one who even comes close to being .500. He did a better job of “pitching to the score” in a low scoring game than any other pitcher in major league history. And it’s not even close.

Of course, that raises the question of why the Dodgers played so poorly behind Koufax.

One reason is that the Dodgers weren”t terribly good batters in general. Their only .300 hitter in 1965 was Drysdale, whose seven homers put him close to the team leaders in that category, who hit merely twelve.

But another reason Koufax won so many 2″0, 2″1, and 1″0 games was that the Dodgers would go out drinking the night before he pitched.

If the starter the next day would be merely Drysdale, Osteen, Johnny Podres, or Don Sutton, they”d get their sleep.

But if Sandy were going to pitch tomorrow, well, you were a Los Angeles Dodger, it was the 1960s, and the night was young.