October 19, 2010

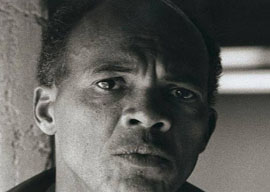

There is a large cohort of educated African Americans who seem to do little else. Mr. Wideman is billed in the byline of the Times piece as “a professor of Africana studies.” He’s examining his blackness all day long and getting a handsome salary for it”and now a fee from the Times. Examining blackness in its billionfold varieties is Mr. Wideman’s job and the job of hundreds of other professors of Africana/Africano/Africani/Africanarum studies.

The unexamined life is, we are told, not worth living. If, like Mr. Wideman, you are one of modern liberalism’s pampered pets with a plush affirmative-action sinecure teaching a made-up pseudo-discipline so that some university can darken up its brochures to the degree required by federal regs, the over-examined life is worth a neat 200 grand a year, plus tenure.

Does John Edgar Wideman know anything about the world other than his own blackness? If I were to pick up one of his books and start in on it, would the words soon shift and blur in front of my eyes “til they just read as Black black black. Black black blackety black! BLACK! blackblackblackblackblackblack …, as happened with the last look-at-my-blackness! book I read? Does he have anything un-black to say to me, in all my shameful un-blackness? To me, as an American? To me, as a man and a brother? To me, his poor earth-born companion / An’ fellow mortal?

In one respect at least I am enlightened after reading Mr. Wideman’s essay. I used to puzzle over the question: Is solipsism a viable point of view? Can one really be so firmly sealed in the prison of self that the color of one’s skin is the primary datum of one’s existence? Now I know the answers.

I’ll tell a train story of my own, not because I nurse any hope of piercing the armor of Mr. Wideman’s solipsism”by definition, nothing could do that”but because I have a hundred or so words to spare in my column allowance.

For seven years I commuted in to New York City on the Long Island Rail Road, an hour each way, Huntington to Penn Station. There were plenty of African American riders. I often had only two or three empty seats to choose from. There were seat partners I avoided: obese persons, obvious drunks, eaters of smelly foodstuffs, persons muttering to themselves, and in the last year or two (this was 1992-99), riders yapping into cell phones. It never crossed my mind though, not once in seven years, to include race as a selection factor. I was looking for a seat on a train, for crying out loud, not a best friend for life.

I don’t of course expect you to believe that, Mr. Wideman. Your own blackness is so infinitely fascinating to you”heck, it’s your living! “ you can’t conceive that it is uninteresting to me or anyone. You imagine (because you can’t imagine otherwise) that your companions in the Acela carriage are thinking about you and your blackness with malice in their hearts all the way from Providence to Penn Station.

Sorry, pal: They’re not even thinking about you with love and respect in their hearts, which I’m guessing would be your distant second preference. The dreadful, inconceivable truth”brace yourself, Mr. Wideman, please”oh, can you bear it?”the appalling truth is that they are not thinking about you at all.