May 30, 2018

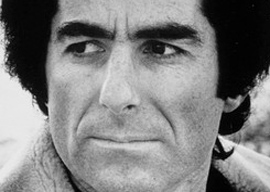

Philip Roth

Source: Wikimedia Commons

But as soon as Wolfe arrived at Yale to pursue his American Studies Ph.D., the satirical genius emerged:

The young Tom Wolfe is intellectually equipped to join some fashionable creative movement and set himself in opposition to God, Country, and Tradition; emotionally, not so much. He doesn’t use his new experience of East Coast sophisticates to distance himself from his southern conservative upbringing; instead he uses his upbringing to distance himself from the new experience.

Of course, Wolfe never went back to the South, becoming a famous sight in the better parts of Manhattan. But he also never lost his self-image as the South’s Avenger.

Wolfe rather enjoyed the best of both worlds in that his resentment of the dominant Northeast fueled his art, while liberals had a hard time imagining that such an important cultural innovator could possibly be as conservative as his countless jibes at them suggested.

Like Wolfe, Roth was also a regional loyalist by nature, in his case to his hometown of Newark, New Jersey.

Roth was a liberal 1940s patriot who fell in love with flyover America from reading Southern and Midwestern gentile novelists such as Thomas Wolfe and Sinclair Lewis. (Although Jews had long prospered in commercial writing, such as radio drama scripts, they didn’t flourish in the most prestigious format, the novel, until post-WWII writers such as Norman Mailer, J.D. Salinger, Saul Bellow, and Roth.)

Roth’s early works tended to satirize his Jewish upbringing. But like many brilliant Jewish intellectuals, as he aged he became more ethnocentric. (This pattern is why the common observation that younger Jews are less chauvinist than older Jews so there is no need to worry about Jewish jingoism because it’s dying out is not wholly persuasive—it’s always been like this.)

This narrowing of interests strengthened Roth’s books as he stopped trying to demonstrate Wolfe-like range and instead concentrated upon endless variations on stories set in mid-century Newark, just as William Faulkner wrote many books about a fictionalized version of Oxford, Mississippi. (Of course, when your beloved hometown is twelve miles from New York’s city hall, you don’t get labeled “provincial” that often.)

On the other hand, Roth’s diminishing interest in the outside world could lead him astray. For example, in his celebrated 2004 novel The Plot Against America, pilot Charles Lindbergh, running on an isolationist Republican platform in 1940, virtually sweeps the solid South.

This is the kind of idea that sounds plausible to many 21st-century liberal Jews but is historically ridiculous. In fact, white Southerners in 1940 were the most gung ho for gearing up to fight Hitler. Nicholas Lemann explained:

The crucial steps before the Pearl Harbor attack that made the United States as prepared for the war as it was—including large increases in military spending, military aid to Great Britain, and the establishment of a draft—would all have been impossible without the enthusiastic backing of southerners in Congress.

While this wasn’t Roth’s finest hour, and the author himself was ambivalent about tarring Lindbergh, whom he considered a genuine American hero, it largely solved for Roth his long-running “Is Philip Roth good for the Jews?” problem.

Comments on this article can be sent to the .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address) and must be accompanied by your full name, city and state. By sending us your comment you are agreeing to have it appear on Taki’s Magazine.