December 12, 2013

Bernard Berenson

For Berenson, as for “the haves” throughout the centuries, life was a kaleidoscopic, multicultural experience, and Cohen conveys the excitement of top-end dealing so well that it’s no surprise Berenson was often reduced to a nervous wreck. One vital element is missing however. We learn who’s buying in detail but rarely who’s selling. Provenance is generally, maddeningly omitted, as though Duveen and Berenson spirited the pictures out of thin air. Berenson’s job, once the pictures were located, was attribution and authentication and he was extremely conscientious about it.

Attribution had long been an approximate affair, bedeviled by wishful thinking. Accuracy now became essential not only to the development of the modern art market but also for other economic activity (e.g., death duties when they came in). A London exhibition of 1897 claimed to include 33 Titians and 18 Giorgiones from private English collections, but out of them Berenson allowed only one Titian and one Giorgione drawing. Later on there was enormous pressure from Duveen to upgrade pictures, but Berenson was “very unyielding” in Mary Berenson’s words. Subsequent accusations against him on this account seem largely ill natured. But Berenson was shy of direct contact with lucre. Mary did the paperwork.

The Wall Street crash ended the golden age, but Berenson carried on climbing. Anti-Jewish politics never took off in Italy, but he hated the National Fascist Party because they were philistines addicted to state control. He stayed in Italy to be with his invalid wife and to protect their home, the Villa I Tatti outside Florence. The property with its fine library and famous research “lists” of pictures consequently remains intact. But even such an Olympian figure as Berenson had to go into hiding after the fall of Mussolini and with the German occupation of Italy.

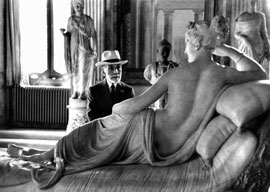

He survived ever more superbly in the postwar era. I think here Cohen could have made more of how his Jewishness added to his stature through his exemplary refusal to fall in to pessimism or despair over human nature. Before the war he had been a celebrity. After the war he became a sage, incredibly generous with his time and property, upholding the abiding values of grace and civilization and the sustaining power of great art, a symbol of what has to endure if humanity is to be anything at all. Princes, politicians, and media stars made pilgrimages to him the way they do to the Dalai Lama.

The story continued to overflow. After his death in Florence in 1959, the women who loved him, and some of the men, all told their versions of this great aesthetic adventure. So did the people who hated him. He was always exposed, never with an official position, either at a university or a museum, and admitted, “I am short of breath intellectually.” So he remained independent, which always arouses suspicion. Harvard had to be persuaded, quite heavily, to accept the gift of I Tatti as a study center. Even Berenson was suspicious, racked with self-doubt as to his own authenticity and yet not above a touch of blatant charlatanism. His own Sketch for a Self-Portrait is one of the more bogus books about him. Rachel Cohen’s is considerably more pure, but far from being the last word.