November 20, 2013

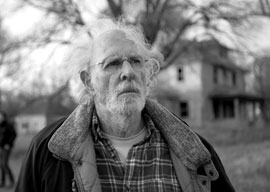

Bruce Dern

While the critics and the Academy have treated Payne very well over the years, he must be aware that his films are always on the brink of a gestalt in fashion in which influential voices suddenly decide that his movies are merely exquisite sitcoms rather than a Crucial Social Message. Perhaps that’s why Payne filmed Nebraska in black-and-white Cinemascope (an obsolete widescreen approach last used for Hud in 1963). It makes Nebraska look Important. (Yet the black and white raises a nagging question: If Woody winds up actually collecting his million dollars, will Nebraska suddenly change to color like that Kansas movie?)

Don’t assume that the Nebraskan director grew up on a pig farm himself. Payne, an elegant man with perfect hair who looks like a debonair version of British actor Steve Coogan, was raised among Omaha’s bourgeoisie, down the street from Warren Buffett. The son of successful restaurateurs, Payne’s birth name is the Platonic essence of Greek-American monikers: Alexander Constantine Papadopoulos.

Nebraska’s star Bruce Dern won Best Actor at Cannes for playing Woodrow T. Grant, a presidential-sounding name that pays tribute to the actor’s background. As FDR’s Secretary of War, Dern’s grandfather was fourth in succession to the presidency. Baby Bruce’s godparents were Adlai Stevenson and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Dern was to the 1970s rather like Kevin Spacey was to the 1990s: the man you loved to hate. For example, as the bully Tom Buchanan, Dern managed to carry some of the otherwise leaden Robert Redford version of The Great Gatsby.

Still, Dern didn’t want to be admired just as the ideal character actor to portray a voluble psycho terrorist with a throbbing vein in his forehead who tries to blow up the Super Bowl with his killer Goodyear Blimp. After he finally got a Supporting Actor nomination for 1978’s Coming Home, Dern didn’t want to be merely the only villain ever to shoot John Wayne (and in the back, too). He wanted to be John Wayne. He wanted to be a beloved leading man.

He still does. Hence, Dern has put the kibosh on entering the less competitive Best Supporting Actor race. He wants the big one, the Best Actor Oscar, so he can finally know that we like him, we really like him.

Regrettably, I’m betting that Dern isn’t going to take home his True Grit-style late-in-life Oscar.

For one reason, voters will slowly decode the tricks Dern uses to make his Woody character so memorable. It’s a theatrically mesmerizing performance somewhat like Dustin Hoffman’s in Rain Man, which has generated no end of complaints ever since about Hoffman winning the Academy Award playing an autistic man.

Dern has already revealed his trick for seemingly unlearning his craft’s fundamental lesson”listen to what the other characters say before repeating your line. When he needed to act oblivious, he would just take out his hearing aids.

Moreover, as an old man only intermittently in touch with his surroundings, Dern has complete freedom to use whatever comic timing Woody needs to wrong-foot the others. He can fail to respond to a question, answer vaguely after five seconds, or instantly deliver a gruff comeback”whatever works best. He’s like Borat telling a “…not!” joke.

Second, Dern himself is not a nearly mute man with only a few fleeting memories. He’s a mile-a-minute talker who never forgets Hollywood anecdotes, marathoning statistics (he estimates he has jogged 105,000 miles), and every broken dream he’s suffered during 55 years in the industry.

During Dern’s first couple of hundred talk-show appearances promoting his Oscar hopes, he”ll likely charm audiences with the contrast between his stricken role and his talkative self. After that, though, his Sally Field-level of emotional neediness may start to wear people down just like it did in the 1980s.