October 16, 2013

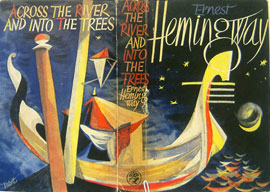

Ernest Hemingway’s Across the River and Into the Trees was published in 1950 to terrible reviews, but I recall that at some point in the past I thought Across the River was the best book he had ever written. Then I picked it up again recently and started reading.

It is the book’s locale”or “terrain,” in Hemingway parlance”which is so appealing. I’m talking about Venice, the Gritti Palace Hotel, and Harry’s Bar. In Across the River, Hemingway described these places referentially. As a backdrop, they are wonderful. The problem is the novel itself…the narration, the dialogue, and the story, such as it is. Across the River is Hemingway’s response to World War II and to where he found himself, half a century old, in the war’s aftermath.

Then there is the New Yorker profile of Hemingway by Lillian Ross in the May 13th, 1950 issue, which preceded the book’s publication. The two are inextricably linked. “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?” is a justly famous profile. It could well be the most entertaining piece ever printed in that magazine.

Lillian Ross catches Hemingway at a snapshot in time”November 16-18, 1949″when he has the draft of Across the River in hand, having landed at Idlewild (now JFK) from Havana with his wife Mary in tow. He was pleased as punch with his work, describing it as the best he had ever done. He would sign a generous contract with Charlie Scribner and deliver the nearly completed typescript before boarding the Ãle de France for Europe. Ross’s method was to tag along as a sort of innocent bystander.

Some might say Hemingway looks and sounds ridiculous. The reason for his exuberance is Across the River. He is ensconced at the Sherry-Netherland hotel, eating caviar and cocktail food out of tins, and drinking champagne with Marlene Dietrich. (“The half bottle of champagne is the enemy of man.”) There are forays to the Metropolitan Museum up the street and to Abercrombie & Fitch, where he runs into his socialite friend Winston Guest. The two commence to shadowboxing.

The profile came out six months later, in May 1950. It created a sensation. It was a bombshell. People wondered whether Lillian Ross had done a hatchet job on Hemingway. It was a difficult call. It could be read either way. Hemingway had fed Ross background material through the mail in the meantime. He claimed not to be unhappy with the result. Whatever misgivings he may have had, Hemingway wrote Ross that “it was a good straight OK piece.”

Then, four months later, The New Yorker published Alfred Kazin’s review of Across the River. Kazin decided that Hemingway had made a travesty of himself. Kazin found the book embarrassing and vulgar. He ended with the backhanded hope, “It is wonderful to know that Hemingway has recovered, and that this book is not his last word.” Equally negative was a review entitled “On the Ropes” in TIME magazine. The anonymous reviewer asserts, “In Across the River, Hemingway never wins a round….Hemingway, at his best one of the few great writers of his generation, gives his admirers almost nothing to cheer about.”

For me the biggest problem with Across the River is repetition. It quickly becomes tedious. The grandiosity is of such high quality as to be stupefying. The red flags start appearing as soon as US Colonel Richard Cantwell (the Hemingway character) is driven over the causeway to Venice and steps into his first gondola. He arrives at the Gritti dock and dismisses his driver. He shouts, “You’re on the town. You can sign here for chow. I don’t want to see you. I’m tired of seeing you, because you worry and you don’t have fun….”

Inside the Gritti, there is an extended exchange between the Colonel and the Maitre d’Hotel. They are members of a diminutive secret society of which the Colonel is “The Supreme Commander.” The Maitre d’Hotel is the “Gran Maestro.” The secret society is an inside joke, of course, and their conversation, mostly about old times and battles, is preposterous. Yet it is meant to be taken seriously and goes on for quite a while. The dialogue is between two supreme beings high up on Olympus.