May 05, 2023

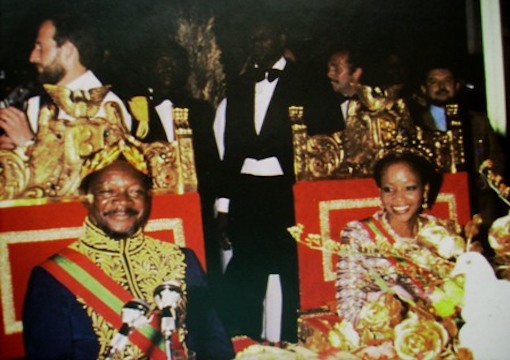

Jean Bedel Bokassa

Source: Wikimedia Commons

If you have a heart in Africa it’s probably not a good idea to read Martin Meredith’s State of Africa because if you do, it will, in all likelihood, break it. In it, he covers, in gory detail, what has happened on the continent in the postcolonial era, and while it’s riveting, it is also deeply disturbing.

Today, the overwhelming view is that colonialism was, at best, an awful mistake; at worst it was a crime against humanity, and those involved, and those who allegedly benefited, should be held accountable in some shape or form.

The recent book Colonialism; A Moral Reckoning by Nigel Biggar, who is Regius Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology at the University of Oxford, provides a balanced and thoroughly researched account of this period that has triggered widespread outrage amongst those (and they are probably the majority) who believe the actions of the European imperialists were mostly malevolent and are simply indefensible. Leading the pack is the usual array of writers, politicians, and academics who seldom miss an opportunity to denigrate what is known as “Western civilization” and its origins. They have leaped aboard the bandwagon to lambaste Biggar with alacrity.

Kenan Malik, writing for The Guardian, is one of many like-minded journalists who can find nothing redemptive to venture about this account. “Biggar has produced something…cartoonish, a politicised history that ill-serves his aim of defending ‘western values.’”

He cites the suppression of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 as proof of typical British brutality, but his main gripe is systemic racism. For Malik, like so many others, “racism” is the supreme evil no matter what the consequences. The fact that these “racists,” in many parts of the world, brought peace and relative prosperity to the people they allegedly discriminated against, is irrelevant. It’s the thought that constitutes the crime; ignore the actions.

In this context it would be enlightening to know what Malik makes of Meredith’s book. If he has the gumption, he might leave aside for a moment what happened during the colonial tenure and study what has happened since.

What does he make of the fact that “by the end of the 1980s not a single African head of state in three decades had allowed himself to be voted out of office. Of some 150 heads of state who had trodden the African stage, only six had voluntarily relinquished power”?

Or the fact that, in the Congo alone, in 1964, over a million people, virtually all civilians, died in sectarian strife. Nobody knows precisely how many more millions have died in the benighted country since. Or that Mobutu Sese Seko, prior to coming to power, had $6 in his bank account. By 1987 a team of editors and reporters from Fortune magazine disclosed that he was one of the richest men in the world at an estimated $5 billion.

Or the fact that Jean Bedel Bokassa “combined not only extreme greed and personal violence…unsurpassed by any other African leader. His excesses included seventeen wives, a score of mistresses and an official brood of 55 children…. [He] also gained a reputation for cannibalism. Political prisoners…were routinely tortured on Bokassa’s orders, their cries clearly audible to nearby residents.” In an effort to compare himself to Napoleon, he declared himself an emperor and spent a large chunk of the national budget on his coronation while his people suffered and starved.

Or the fact that Uganda’s Idi Amin, in a bid to crush political opposition, ordered the gruesome deaths of thousands of alleged opponents at the hands of his “death squads.” “The Chief Justice was dragged away from the High Court never to be seen again. The university’s Vice Chancellor disappeared. The bullet-riddled body of an Anglican Archbishop, still in ecclesiastical robes, was dumped at the mortuary of a Kampala hospital. One of Amin’s former wives was found with her limbs dismembered in the boot of a car. Amin was widely believed to perform blood rituals over the bodies of his victims.” He was heard on several occasions boasting about his penchant for eating human flesh.

Or the fact that foreign researcher Robert Klintberg reported on oil-rich Equatorial Guinea as being “a land of fear and devastation no better than a concentration camp—the ‘cottage industry Dachau of Africa.’” Under Macias Nguema, more than half of the population was either killed or fled into exile. Finally deposed by his nephew, Obiang was indicted for the murder of 80,000 people. The plunder continued.

Or that in Nigeria, between 1988 and 1993, an official report estimated $12.2 billion was “diverted” from the fiscus. In 1990, the United Nations concluded that Nigeria had one of the worst records for human deprivation of any country in the developing world.

These are only a smattering of an almost endless litany of entirely avoidable man-made catastrophes that have blighted Africa since the imperial exit. One is left wondering if there is any precedent in history for such calamitous misrule that has led to the early, often violent deaths of millions, and delivered unspeakable misery to hundreds of millions more, which is where we are today.

Having read the book, I’m left pondering the fact that Cecil Rhodes, a colonial colossus, looms large in contemporary history as one of the great villains of the last century, better known for his alleged malfeasance than any of the abovementioned leaders. But as far as I know, Rhodes never stole from anyone and never killed anyone, and he certainly didn’t eat anyone. I know he did use his money and military muscle to stop slavery and intertribal slaughter. And I know he plowed most of his fortune into building roads, railways, educational facilities, and other infrastructure needed to transform a wilderness into a developed country. It looks to me like his generosity of spirit is reflected in the Rhodes scholarships he provided for, aimed at nurturing the talents of a select few from across the racial divides in a bid to make the world he was leaving a better place.

I think the story of the white man in Africa is one of damned if you do, damned if you don’t. The Europeans have taken their lumps and left. The Chinese are here now, and they are not well-known for being nice to the natives.