February 10, 2024

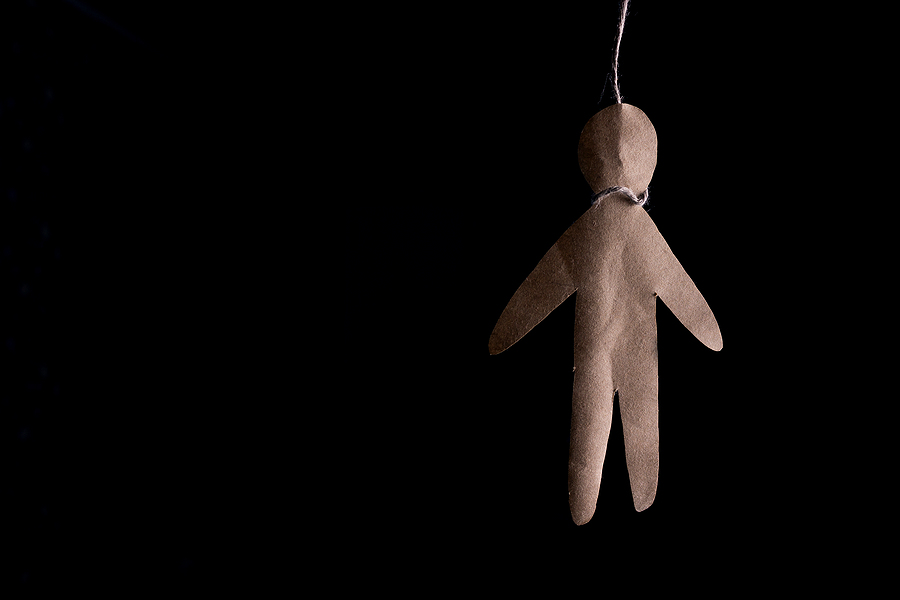

Source: Bigstock

Viscerally, I am in favor of the death penalty, but in more sober reality I am against it. There are some crimes so heinous, so beyond all extenuation, that death seems the only just punishment; but justice is not the only desideratum in human arrangements, so this is not a decisive argument.

I would not be prepared to execute someone myself in what might be called cold blood: that is to say, not in immediate self-defense. It seems to me that I cannot depute to others what I would not be prepared, for both ethical and psychological reasons, to do myself. It follows that I cannot support the death penalty.

There is also the question of error. All jurisdictions, no matter how scrupulous their deliberations, make mistakes, and to execute an innocent man (that is to say, a man innocent of what he is charged with having done) is peculiarly terrible. The fact is that innocent men have been executed. No utilitarian argument, such as that some murderers will go on to kill others if they be not executed, and that the number of the wrongly executed will be smaller than the number of those killed by murderers who were not executed, can excuse wrongful execution. Rather, this is a refutation of utilitarianism as a moral theory.

Nevertheless, I accept that decent people can have a different opinion from my own. I find it difficult to believe, however, that a decent person would not be appalled by the recent execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith in Alabama by asphyxiation with nitrogen, at least if reports of the execution bear any resemblance to the reality of it.

It put me in mind of what my friend, or friendly acquaintance, Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian writer, was reported to have said when the first four attempts to hang him (he had been sentenced to death by a kangaroo court on trumped-up charges) failed: “In this country,” he said, “they can’t even hang a man properly.”

The whole episode in Alabama was appalling. Smith murdered Elizabeth Sennett in 1988, having been paid, with others, to do so by her husband. No one disputed the fact of his having done so, or the extreme brutality of his crime. He was first sentenced to death in 1989; he was then retried and sentenced again to death in 1996.

In 2022, he was due to be executed by lethal injection, but because the executioner could find no vein through which to inject the lethal drugs, the attempt was abandoned. It was only this month that he was executed by an experimental method.

Apparently, he took 22 minutes to die, and for several of them he was still conscious. The Alabama corrections commissioner, a man called Hamm, said that it was Smith’s own fault that he took so long to die, because he attempted to hold his breath rather than breathe in the nitrogen. All I can say is that I am glad I am not a prisoner on one of Mr. Hamm’s prisons.

After Smith’s death, the governor of Alabama, Kay Ivey, said, “After more than 30 years and attempts to game the system, Mr. Smith has answered for his horrendous crimes.” It seemed not to occur to the governor that there might be something wrong with a system that could be gamed for thirty years, and that the fault lay with the system, not with the person, however wicked he might once have been, who was struggling to preserve his own life, which is surely a natural thing for him to have done.

The murder victim’s son, who witnessed the execution as he was permitted to do, said, very understandably but also mistakenly, “Elizabeth Dorlene Sennett got her justice tonight.” But it was not she who got justice, since she no longer existed; it was her survivors and society in general who, if anyone, got their justice.

Besides, justice delayed, especially for so long a period as 34 years, is justice denied. No system of justice that executes a man after a third of a century of having him in its custody is anything but a disgrace. The delay is not a manifestation of legal scrupulosity, but of legal incompetence. As Macbeth put it in another context, “If ’twere done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.” If it takes more than thirty years to satisfy yourself that a man should be executed, he should not be executed—even if you believe, in the abstract, in execution as a just and decent punishment.

That there is officialdom that fails to see the wrongness of this manner of proceeding, and is prepared to justify it, is horrifying.

If Smith were to be executed, he should have been executed within two weeks of his sentence. He had a right of appeal, but the evidence against him was overwhelming, and he was guilty without a shadow of a doubt.

The method of execution employed was also very alarming, pointing as it does to more than mere legal incompetence. In fact, it was scandalous. I was pleased to see that at least there was very little experimental evidence relevant to execution by nitrogen, but if I had been asked whether I thought such a method of execution was a good idea, I should have said no. I think that the man in the street would also have said no.

It seems that the ability to kill a man quickly who has been judicially sentenced to death has now been lost in some parts of America: as, apparently, have other, perhaps more generally useful, skills. This loss of competence is not confined to the United States: It is evident across the whole Western world, in small things as in large. It is as if the West has lost the mandate of heaven, as the Chinese call it. We have trained too many people whose only possible employment is the obstruction of other people’s work by legal or bureaucratic regulation; and competence is not merely a matter of skill, but of attitude and habit. An incompetent execution is, if I may so put it, a canary in the mine, albeit that the canary is a warning of a different gas from nitrogen.

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Ramses: A Memoir, published by New English Review.