February 15, 2024

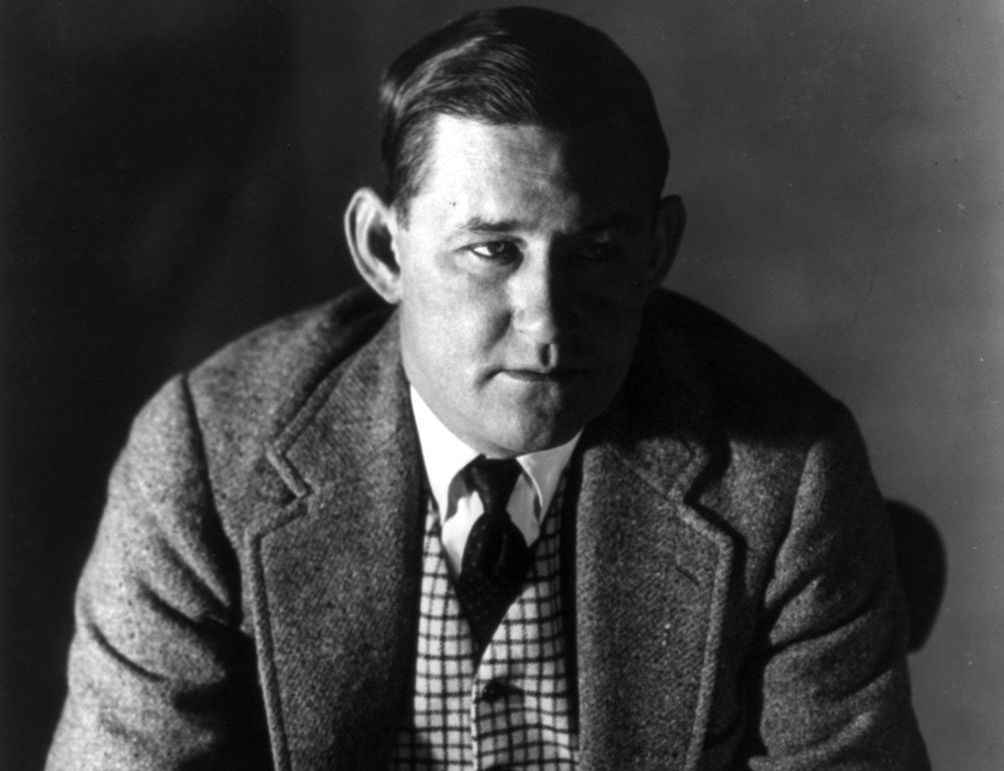

John O'Hara

Source: Public Domain

I’m back scribbling about writing again because penmanship is like cocaine—once you start it’s difficult to stop. Disaffection is my customary response to contemporary writers and literature—long-winded me-me-me balderdash—and I won’t go near hysterical American female screeches who pass for writing from know-nothings at The New York Times.

So, everyone I mention in this column is, alas, dead, but their writing continues to enthrall and fascinate, as well it should. I never read Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange but have always admired him, and more so after I got hold of his Mozart and the Wolf Gang. Written partly in prose, partly in verse, it is a kaleidoscope of snatched conversations between Wolfgang and other geniuses up in heaven. Not my cup of tea, but Burgess is as perceptive as they come, and his use of language is unequaled.

Try this as an opening by Burgess on music and musicians: “Waking crapulous and apothaneintheloish, as I do most mornings these days, I find a little loud British gramophone music over the bloody mary helps me adjust to the daily damnation of writing.” Would you call this an arresting first sentence? Apo-what? Being Greek, I wasn’t fooled by old Anthony. The tongue twister means “I want to die.” Ancient Greek was laconic, and one word did the trick.

Opening sentences are famous for their brevity—“Call me Ishmael”—although my favorite is by Barnaby Conrad, a great gent and friend, amateur bullfighter, boxer, and wonderful writer: “On September 22, 1947, in Linares, Spain, a multimillionaire and a bull killed each other, and plunged a nation into mourning.” I may have the date of the month wrong, but the rest is kosher. That’s what I call an opening. It’s The Death of Manolete, the greatest bullfighter ever.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that writing followed the Greeks, whose teachings and philosophies were mostly oral. Today no one writes, they type or text, and they certainly don’t write love letters. But just try to imagine what the world would have been like if pencils had never existed, or pens, or paper, no typewriters nor printing presses. What kind of a world would we be living in now without those? My only and great regret is we didn’t stay that way, without computers or word processors, no email or internet, and no social media. In one of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates recounts a story in which an Egyptian god has invented writing and is admonished for it: “This discovery will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls because they will not use their memories.” If only old Plato could see us now, with people unable to string two words together except when quoting from a hamburger commercial. Plato, however, was aware of writing’s social value. Always in one of his dialogues, he has the great Athenian lawmaker Solon made to feel shame by the Egyptians because they know through writings more about the Greeks than the Athenian.

Then there is the theory that adopting literacy in ancient societies fundamentally reconfigured the human brain. If it did, it certainly is undoing it now with all the garbage online. Literacy for the ancient world is like the internet for us, say left-wing pundits, who also inform us that preliterate societies were matriarchal and worshipped the Goddess and feminine values. The written word propelled culture toward linear, left-brained thought and brought about the ascendancy of patriarchal rule and misogyny.

And speaking of total left-wing bullshit, Hollywood has never managed to appreciate great writing, and why should it? The medium is made for morons, as the written word is not easily visually turned into its equivalent. Both Faulkner and Fitzgerald failed, and Hemingway never even tried despite some pretty good offers from Hollywood. These scummy types showed their contempt for writers with their jokes, the most revealing being about how dumb a blonde was: She f—ed the writer rather than the producer.

Thomas Hardy’s first wife, Emma, bitterly complained: “He understands only the women he invents, the others not at all.” Well, yes, that’s how most writers are, or were. In today’s world we are documented and ultra-surveilled, our movements, purchases, step counts carefully recorded. Writing is no longer an act of creation because of too much information. The first time I read Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, I was left dumbfounded by the beauty of his description of the prince. Prince Salina’s masculinity, nobility, fairness, and adoration for the fairer sex had me yearning for that noble period. Years later, another nobleman, Luchino Visconti, director of the movie, exclaimed: “I cannot understand how a Bronx-born acrobat can play Prince Salina as close to the real thing as he does.” He was referring to Burt Lancaster playing the prince like the real thing. But leave it to Burt, he could do anything and did.

I loved discovering great writers when I was young. The novels of John O’Hara, his short stories, and the characters I’d meet in nightclubs that were straight out of his works. And authors like James T. Farrell, and John Steinbeck, and Theodor Dreiser, and their characters that were formed by the emotional consequences of money’s absence. Those were the days, my friends, and they’re not coming back. Now we have a woman whose best-selling true story is how she had threesomes and foursomes with her husband and they helped keep a sound marriage together. It was favorably reviewed by the Times; in fact most of the people who work for that rag were very jealous, and I don’t blame them, as I’ve seen some of their wives.