October 30, 2013

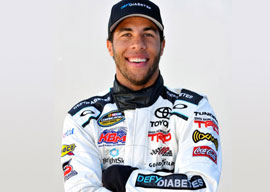

Darrell Wallace, Jr.

So why are the top ranks of NASCAR drivers less integrated today than in the 1960s? Why in 2013 is Wallace being adamantly celebrated by NASCAR as the exception to the rule?

The usual explanation is the usual: prejudice, discrimination, Jim Crow, slavery, etc. But why would the effects be worse than in Wendell Scott’s day?

Moreover, NASCAR doesn’t represent an isolated trend. In a striking number of fields, the barrier-breakings of the past haven’t led to much difference today.

Look at women in racing. Shirley Muldowney was the champion fuel drag racer of 1977. (A movie about her, Heart Like a Wheel, was released in 1983.) Yet 36 years later, so little has changed that Danica Patrick can still make $15 million annually for being The Girl Driver.

Similarly, five black golfers won 23 PGA tournaments between 1961 and 1986. Since then, only the quarter-black Tiger Woods has triumphed.

Conversely, African Americans have come to utterly dominate the running back position in the NFL while largely losing interest in baseball.

It wasn’t supposed to turn out this way. The reasonable-sounding expectation back in the 1960s as discrimination faded was that accomplishment would become ever more randomly scattered among the population. Instead, achievement in America is perhaps becoming more hereditary, more channeled by descent.

Yet it’s culture as much as DNA that is pushing the new de facto segregation.

Examples such as Scott of what I call “diversity before Diversity” point to an unanticipated nature-nurture paradox. While nurture (such as Malcolm Gladwell’s popular 10,000 Hour Rule) is usually seen as the nice, liberal alternative to retrograde, politically incorrect nature, the last few decades point to increasing nurture by sideline fathers and tiger mothers boosting segregation.

From the perspective of 2013, it’s starting to look as if 20th-century society was an anomalous free-for-all in which talented upstarts such as Scott could climb the ladder, in part because it wasn’t all that steep. NASCAR racing in 1963 was far cheaper than today. Thus, like the golf tour back then, it featured fewer prefab stars and more raffish outsiders.

Auto racing has always featured dynasties, such as the Earnhardts, Andrettis, Unsers, and Pettys. But racing used to be seen as the exception, not the forerunner.

After an era of “careers open to talent,” the world seems to be settling down again to a social system in which high achievements require multigenerational investments, and thus are largely passed down within families and ethnicities.

For example, back in the Bad Old Days, Lee Elder, the first black golfer to play in the Masters, got his start as the chauffeur (and ringer) for America’s most notorious gambler/conman Titanic Thompson. A Lee Elder biopic would be far more entertaining than one about Tiger Woods, whose youth consisted of endless golf under his father’s calculating eye. But Tiger’s upbringing is likelier to generate a star (or a burnout).

Even today’s esteemed exceptions to the rules often turn out to be unexceptional. For example, young Wallace, last weekend’s winner, is not some genetic fluke who has emerged straight outta Compton to compete in NASCAR on raw talent. The North Carolinian’s father had him racing by age 9. At 12, the family entered him in 48 Bandolero events, with the youngster winning 35 times.

Racially, Wallace is always described as black, but ethnically he’s a good old boy. Unsurprisingly, he has a white Southern father, a white Southern accent, and a white Southern Twitter handle: @BubbaWallace.