May 04, 2024

Source: Bigstock

One of the things that I notice walking through the streets of England—but not only in England—is the almost complete lack of self-respect of the population. Self-esteem, of course, is another matter entirely: Most people are on the qui vive for anything that they think might be regarded as an assault on their dignity as the bearer of human rights, ever growing in number, complexity, and self-contradiction.

Not only do people fail to make the most of themselves, they seem determined to make the worst of themselves, as if they were setting a challenge to others not to remark on them or pass a judgment about the way they look. In England, fat young women (of whom there are lamentably many) squeeze themselves into unbecomingly tight costumes, like toothpaste into a tube. It is as if they were intimidating you into not noticing how hideous they look.

On an escalator in a station recently, I followed a very fat young woman. At the bottom of the escalator, she was eating some kind of nut bar, no doubt advertised as health-giving, as if she were urgently in need of nutrition. By the top of the escalator, she had taken out her telephone and was sending a message with astonishing dexterity: She could type faster on her tiny keyboard than I on my computer. From the look on her face, I judged her to be of good or even of superior intelligence. Her bad taste was not the consequence of intellectual incapacity.

Her black two-piece outfit clung to her body as closely as one wraps leftovers in cling film before putting them in the fridge. Between the upper and lower halves of the costume, however, was a kind of strait separating two continents, through which pudgy white flesh bulged. On the small of her back (not very small) was a tattoo. Naturally, her face was pierced with rings and other metallic adornments. She presented herself to the world with an almost ferocious, and certainly deliberate, absence of dignity.

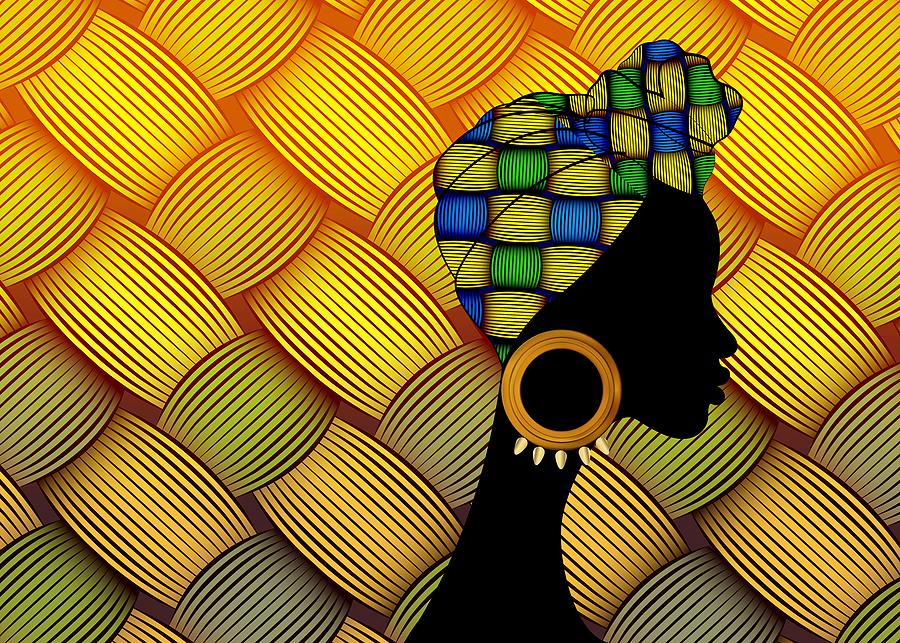

Being fat is not by itself incompatible with dignity. I think, for example, of the fat market women of West Africa, in their long cotton gowns and magnificent turbans. When they move, they are stately, like the galleons of the line of an early navy. One respects them immediately.

There is an epidemic of self-abuse in the Western world, worse no doubt in the Anglo-Saxon parts than elsewhere, but spreading, for the world follows American trends with all the intelligence of a headless chicken. There have always been scruffy people—I was once one myself—but the mass adoption of ugliness as a fashion and way of being is something relatively new. It bespeaks a toxic mixture of self-hatred, narcissism, solipsism, and laziness.

The natural beauty of people presumably falls on a normal, or Gaussian, distribution, the vast majority of people falling somewhere between great beauty and great ugliness. But no one is, or very few people are, condemned to indignity. We adopt indignity as a way of being.

There are, of course, certain advantages to ugliness and indignity as goals. They are targets almost certain to be hit, requiring practically no effort. To turn oneself out well takes continued and continual effort, and while it may become second nature, it still remains a discipline that imposes its obligations.

Carried to excess, of course, it becomes vanity, which in some cases may be preposterous. Dandyism is often laughable. But the opposite is worse and is also a form of vanity, a worse form. What it suggests is the following: that I am so essentially important or good a person that I need not make an effort for others—you must therefore accept me as I am. This entails that I must accept you as you are, and hence the general level of self-respect declines, to be replaced by self-esteem. The former is a social quality—it requires seeing oneself through the eyes of others—while the latter is purely solipsistic.

I changed my views on mode of dress in Africa. Until then, I had taken the standard bohemian line that smartness of dress was nothing but the means by which a social class imposed its hegemony on the rest of society, and also that concern with dress was essentially trivial and superficial.

But in Africa I saw people who were far poorer than anyone I had ever met turn themselves out, whenever they could, with pride and care—and succeed magnificently. They did so even though it cost them great effort and even sacrifice. It was a triumph of the human spirit, a local defeat over the second law of thermodynamics. It changed my attitude to dress thereafter.

The deliberate self-uglification of people is a form of bullying. It is the demand that you do not notice something that you cannot help noticing. Comment upon it would be even worse. The only defense is to reply in kind, to be just as ugly, or at least as sloppy.

Personal ugliness is democratic, for its achievement is easily within the reach of all, while personal beauty is aristocratic because its achievement is not within the reach of all and is in part determined by heredity. Such ugliness, therefore, is politically virtuous in a way that beauty can never be. One displays one’s solidarity with the rest of mankind by uglifying oneself, whereas one displays one’s inegalitarianism by trying to be anything other than ugly, for example elegant.

This applies not only to dress but to tastes in other things. Of course, there is a large element of playacting and hypocrisy in all this. The rich man who dresses in proletarian fashion has no intention of sharing his wealth with the proletariat, quite the reverse, he is usually avid for more. He may also mix his message, for example like Donald Trump: by wearing a suit and tie but donning a baseball cap. No man, said Doctor Johnson in Rasselas, may drink simultaneously of the source and the mouth of the Nile, but for various crooked reasons the bourgeois may try to appear proletarian, the better to head off envy, criticism, or revolutionary sentiment. So far, at any rate, the ruse has worked.

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Ramses: A Memoir, published by New English Review.