March 31, 2017

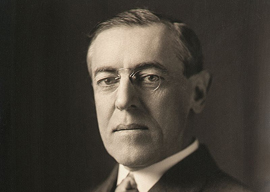

Woodrow Wilson

William F. Buckley spent his adult winter months in Rougemont, an alpine resort next to its chicer neighbor Gstaad, now a mecca for the nouveaux riches and vulgar. Throughout the “60s and “70s, however, the area was known for its music festival run by Yehudi Menuhin, and for celebrity writers like Bill Buckley, my mentor, and others such as John Kenneth Galbraith and actor-turned-author David Niven.

The Buckley household entertained nightly, Bill and Pat being experts at mixing those of us who knew little with cultural icons such as Vladimir Nabokov or his son, Dmitri, both of whom were occasional visitors. Postprandial entertainment was provided in Bill’s downstairs studio, where everyone was required to paint a picture. (Teddy Kennedy painted a bridge two years after Chappaquiddick.) After 2000, toward the end of his life, and after Bill had allowed the neocon infiltration of the conservative party by such American “patriots” as Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol, he no longer painted but indulged in a game where each of his guests opined whom they considered the worst American president to have served that office.

When my turn would come”and Buckley always kept me for last during countless dinner parties”I always answered either Woodrow Wilson or Abraham Lincoln, although the former was a far bigger hypocrite. (And unlike Abe, he did not pay for his crime of going to war and misleading the nation.) My theory was and is that professors make lousy leaders, and no one caused more harm than the ghastly Wilson. Dishonesty and hypocrisy are twinned in academia with patched elbows on tweeds and polka-dotted bow ties.

America entered the arena of world politics in 1917 by interfering in a European war, and inadvertently helping upset the applecart in Russia. Seventy years later, the collapse of communism marked the intellectual vindication of American ideals, handing Uncle Sam a moral authority that is deserved but hardly adhered to by other nations. (I spent my youth traveling in countries that hate America with a passion, places like the Middle East, South America, Southeast Asia, and Africa.)

So, how can the hysterical New York Times work itself into a frenzy with that recent phony headline about “The loss of U.S. moral authority”? What universe is the Mexican-owned Times living in? Uncle Sam, however fairly or unfairly, is among the most hated symbols on earth, which brings me to the point of my story: What has the good uncle done to deserve this? Envy is obviously one reason, or where the French”among the most anti-Yankee people I know despite two trips overseas by American boys to save French bacon”are concerned, American anti-intellectualism as illustrated by McDonald’s. Basically, however, these are petty points more suited to a high school debate. The main reason for the lack of moral authority of the U.S. is interference in other nations” affairs.

As Henry Kissinger wrote in Diplomacy, “For as long as Americans have ascribed Europe’s travails to the balance of a power system, its leaders have looked askance at America’s self-appointed mission of global reform.” Like petulant children, European nations were not best pleased to be lectured by Woodrow Wilson and his Fourteen Points in Versailles. Forty years later, the Vietnamese were just as displeased to be told by Americans to practice democracy and stop hiring family members for civil posts. Twenty years earlier, Guatemalans, among other South Americans, saw their elected leaders overthrown by people financed by the CIA, and in 1961, the butcher that was Fidel Castro became a hero overnight by repelling a CIA-financed and badly organized attack by anti-Castro Cubans living in the good old US of A. I could go on.