September 24, 2021

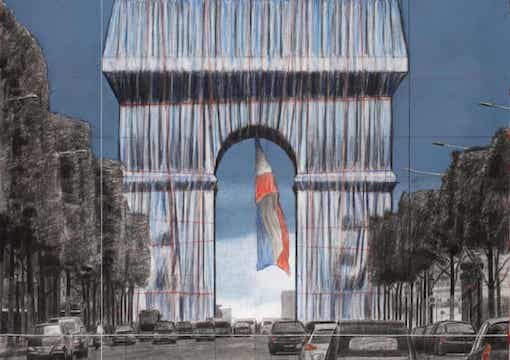

Source: 2019 Estate of Christo Javacheff

I have noticed that, in all the acres of commentary (most of it respectful or even laudatory) on the wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris with 25,000 square meters of polypropylene fabric, none has claimed that the beauty of the city has been thereby enhanced. It has been called “remarkable,” “amazing,” “bold,” and even “artistic”—O Art, as Marie Antoinette would now exclaim, what crimes are committed in thy name! But no one—at least, no one whose cowardly dithyrambs to this costly, pointless exercise I have read—has called it beautiful. It is a case of the Arc de Triomphe’s new clothes.

The artist posthumously responsible for this absurdity, Christo, said that the whole point of it was its pointlessness. But if the pointlessness of something is its point, it has a point and is therefore not pointless (a version of the Cretan liar paradox). Of course, the mere fact that something has a point does not make it worthwhile; many points are not worth making.

The evasion of aesthetic judgment on the whole enterprise is both significant and by now customary. The word beauty and its cognates have been all but expunged from the vocabulary of critics, almost as completely as a certain word referring to a race of human beings has in literature and the title of an Agatha Christie novel.

In the case of architectural writers, this is perhaps not surprising: There is so little to which the word, rather than its opposite, could be applied. But in fact the whole category of aesthetic judgment has been sidelined by those whom one would most expect, and who one would think were most qualified, to make it.

This is not principally because there is a paucity of objects on which to make it. The world is as full of such objects as ever. Indeed, it is my contention that, at least in the privacy of one’s own minds, it is inevitable that we should make such judgments, just as we inevitably make judgments about the morally good and bad. It is part of what being human is.

However, we can conceal our judgments from others, and that is precisely what writers about art and architecture now do. The reason for this is not merely that, there being so little produced that is worthy of positive aesthetic judgment, they wish not to sound like disgruntled dinosaurs, unable to keep up with the latest developments. It goes deeper than that.

To reveal your taste, to say what you find beautiful, is to expose yourself to others—to their ridicule and contempt more often than to their admiration. The fact is that we live in an age in which people like endlessly to talk about themselves, but without revelation, without making themselves vulnerable. If I say that I find x beautiful, I risk the disdainful reply, “Oh, really?” I have thereby exposed myself as someone of poor or worse judgment. I have demonstrated that I am an unsophisticated, reactionary, ignorant, or conventional person. And it is a convention that to be conventional is the worst thing a person can be, at least worst in certain circles.

Little reveals more about us than our aesthetic tastes, which is why so many people herd together for safety when it comes to making judgments. The safest procedure, of course, is to make no judgments at all, the technique of most writers on artistic and architectural subjects today. They are like those gnus that move in vast compact herds in search of new grazing. If they break from the herd, they are in danger of being picked off by the prowling lion.

The unwillingness to express aesthetic judgment does not, of course, reduce them to silence, any more than the resort to mere psychobabble means that people cease to talk about themselves; on the contrary, it leads to an inflation of verbiage.

If you overhear people talking about themselves—the one subject about which you might have expected them to be expert—they often, or usually, do so in a strangely objectified way, almost as if they were not themselves but some other person, a third party. As art critics talk without making aesthetic judgments, so people talk of such things as their brain chemistry, though they have no idea of what it is and have not the faintest idea of how it may be investigated. Needless to say, when they objectify themselves in this fashion it is to explain something bad, unpleasant, or unwanted about themselves. Nobody speaks about his brain chemistry in describing a generous or charitable act, or why he helped an old lady across the road.

In other words, we have a tendency to put a theoretical filter or lens between ourselves and real self-reflection or self-examination. This filter or lens is usually some silly or ill-understood theory that prevents seeing ourselves in an undistorted fashion. One of the functions of the filter or lens is automatic self-exculpation. While it supposedly helps us to understand ourselves, in fact it does the opposite: It prevents us from knowing ourselves, for self-knowledge is always disturbing. This is why psychology has contributed so little to human self-understanding since it first became a subject, or object, of separate study, and why the vast increase in the number of psychologists has not led—to put it mildly—to a reduction in the level of psychological distress. Psychology, other than the self-reflective kind, is the enemy of truth, even if it discovers some truths.

The blathering that has accompanied the wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe reminds me of psychological blathering: Its object is to disguise the unpleasant truth, in this case that the Western artistic tradition, at least that part of it that attracts media attention, is dead. The resort to the pointless wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe is proof of it. And yet, without claiming that we live in an artistic golden age, I know of artists whose work is certainly meritorious. It is the bane of hyper-publicity that is so destructive, that turns stuntmen into supposed artists. The Arc de Triomphe will emerge from its wrapping as Houdini emerged from his chains.