May 22, 2019

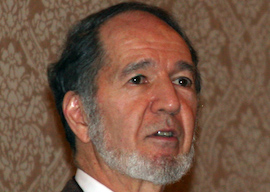

Jared Diamond

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Jared Diamond, who became a famous public intellectual when his 1997 best-seller Guns, Germs, and Steel was widely proclaimed to have refuted The Bell Curve by arguing that the variation in achievement among races today is a cultural side effect of ancient differences in agricultural potential among the continents, is now under fire for himself being white.

The Boston-born Diamond, who wears his beard in that peculiar Amish look of Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick (Harvard political scientist Robert D. Putnam, whom Diamond cites admiringly, is another Ahab-bearded academic), is now himself the subject of the ongoing hunt for the Great White Male.

In a New York Times review of Diamond’s latest tome, Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis, critic Anand Giridharadas angrily denounces Diamond’s lack of diversity. The South Asian reviewer implies that Diamond is part of a back-scratching coterie with Steven Pinker and Yuval Noah Harari, who, by blurbing each other’s airport bookstore best-sellers, conspire to keep “women and people of color” from getting “an opening to publish a book with a serious publisher.”

I began to wonder why we give some people, and only some, the platform, and burden, to theorize about everything.

The “some people” who arouse Giridharadas’ ire are Jewish moderates (Upheaval is one of the few books published in 2019 that doesn’t include a ritual denunciation of Donald Trump) of a scientific and Darwinian bent.

Diamond has been a polymath professor at UCLA since 1968. He started off in physiology, in the footsteps of his father, Louis Diamond, a medical researcher who discovered a number of hereditary blood disorders. Diamond’s dad, “the father of pediatric hematology,” was a great man. His New York Times obituary said a transfusion technique he invented in 1946 “is credited with saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of babies.”

The son then moved on to ecology in 1980, and since 2000 teaches geography.

Diamond speaks a half-dozen languages (including Finnish and Bahasa Indonesian) and has lived all over the world, most notably in New Guinea with its extraordinary human diversity.

The birth of his twin sons in 1987 inspired him to take up yet another career as a popular science and history writer. I found his 1991 collection of magazine articles, The Third Chimpanzee, an early venture into evolutionary psychology, inspiring in my own writing career.

Diamond hit the jackpot with his 1997 follow-up Guns, Germs, and Steel. While not exactly refuting The Bell Curve (Diamond has many talents, but quantitative skills are not among them), it at least brought up the kind of ideas that guys like to argue about.

In particular, Diamond’s famous contention that there is something about the African elephant that made them impossible to use in warfare (what war elephants have to do with The Bell Curve is a long story) has proved endlessly fascinating to the male mind. I don’t know how many dozen times since then I’ve gotten into discussions of which exact species of elephant Hannibal took on his march through the Alps to invade Italy.

Ever since, Diamond has been popular with tech billionaires and the like, who enjoy Diamond’s scientific arguments for the politically correct position they need to believe in for their own safety, far more interesting than the derisible Theory offered by postmodernist academics.

For example, Upheaval is No. 1 on Bill Gates’ latest summer reading list. The world’s second-richest man writes:

I’m a big fan of everything Jared has written, and his latest is no exception. The book explores how societies react during moments of crisis. He uses a series of fascinating case studies to show how nations managed existential challenges like civil war, foreign threats, and general malaise. It sounds a bit depressing, but I finished the book even more optimistic about our ability to solve problems than I started.

Diamond’s popularity with the movers and shakers has made him a hate object among cultural anthropologists, jealous that nobody pays attention to them anymore.

In Upheaval, Diamond, now in his early 80s, indulges in his penchant for grandfatherly good advice. His previous book, The World Until Yesterday, was a sort of self-help book about what could be learned about domestic problems from New Guinea tribesmen.

This new book offers nation-help lessons derived from the places he has lived, such as Chile, Indonesia, Australia, and West Germany. His wife is a clinical psychologist who specializes in a fairly hardheaded form of quick counseling for people in emotional crises, so he has framed the book as a study of nations in crises.

Diamond begins with two success stories: 19th-century Japan and 20th-century Finland. Japan’s impressive response to the arrival of the American black ships in 1853 is well-known, but how Finland escaped being conquered and occupied by Stalin’s Soviet Union is less so. After fighting superbly when the Soviets invaded in 1939, postwar Finland had to humiliate itself by following the Soviet lead in its foreign policy. But Finland, unlike the rest of Eastern Europe, kept its domestic freedom.

Diamond identifies “a strong national identity” as a shared advantage possessed by both nations, with their unique languages and relative ethnic homogeneity. Diamond is impressed by the we’re-all-in-this-together patriotism of Finns and Japanese. As one of the last American intellectuals who can remember Pearl Harbor 78 years ago, he fears that contemporary Americans are losing the national solidarity of the mid–20th century.

On the other hand, history is less of Diamond’s strong suit than is geography. Thus, my favorite bit of the book is when Diamond pauses the political narratives to offer a Guns, Germs, and Steel-style explanation of why the soil of the Upper Midwest is so fertile:

Ice Age glaciers…repeatedly advanced and retreated over the landscape, grinding rocks and generating or exposing fresh soils.

So that explains why even the rainy parts of Texas aren’t great for farming: The glaciers seldom got that far south to pulverize the soil.

Because of North America’s tapering wedge shape, large volumes of ice forming in the broad expanse at high latitudes were funneled into a narrow band and became heavier glaciers as they advanced toward the lower latitudes.

In contrast, few parts of the tropical world were glaciated, and therefore have to rely on floods and volcanoes for good farmland.

Diamond’s most interesting book remains The Third Chimpanzee, probably because he had a magazine editor to quell his pedantic impulses. Also, Diamond has had a big influence on the conventional wisdom of the past quarter century, so his natural tropes are old news by now. Plus, he’s not naturally as forceful of a stylist as is, say, historian Paul Johnson. In this book, Diamond employs a casual prose style that won’t intimidate casual readers by conveying too many ideas per page, but it struck me as verbose.

Diamond is aware that his realism and ability to compare and contrast mark him as a potential crimethinker. For example, he made famous an aerial view of Hispaniola where you can see the national border between deforested, eroded Haiti and verdant Dominican Republic. In his 2005 book about ecological negligence, Collapse, he even dared suggest that the DR dictator Trujillo’s policy of welcoming white immigrants contributes to it being less dystopian than Haiti.

In contrast, Diamond mostly keeps his skepticism about mass immigration under wraps in Upheaval. If you read page 414 very carefully, you’ll notice that Diamond points out that immigration from the Third World to the First World worsens environmental problems such as carbon emissions and overconsumption of resources. But I doubt if many will notice anything amiss.

On the other hand, Diamond’s promotional interviews have been more frank. He told The Guardian that on immigration policy he’s on the same side as Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán:

“There are about a billion Africans in Africa and almost all of them would be better off economically and politically and in terms of personal safety in Europe,” he says. “The cruel reality is that it’s impossible for Europe to admit a billion Africans but Europeans will not acknowledge this conflict between ideals and reality.”

So why the distinction between what the very smart Diamond worries about in his own mind and what he puts in his books? Blogger Paleo Retiree offered an acute if uncharitable theory at Uncouth Reflections:

…Diamond revealed that he took up writing the big books for the popular audience when he became a parent…. He’d simply come down with what afflicts so many people when they have kids: a bad case of the Worthies. Where his big books go, his main concern hasn’t been to share his knowledge and his thinking. It’s “What shall we tell the children?” My conclusion: maybe Diamond’s books are best taken as morality fables for overgrown kids.

Alternatively, you could say that Diamond wants to live up to his father’s example, which is a noble ambition. In any case, with the growing extremism and lunacy of the Current Year, Diamond’s old-fashioned aspiration to wise elderhood has become refreshing.