April 10, 2024

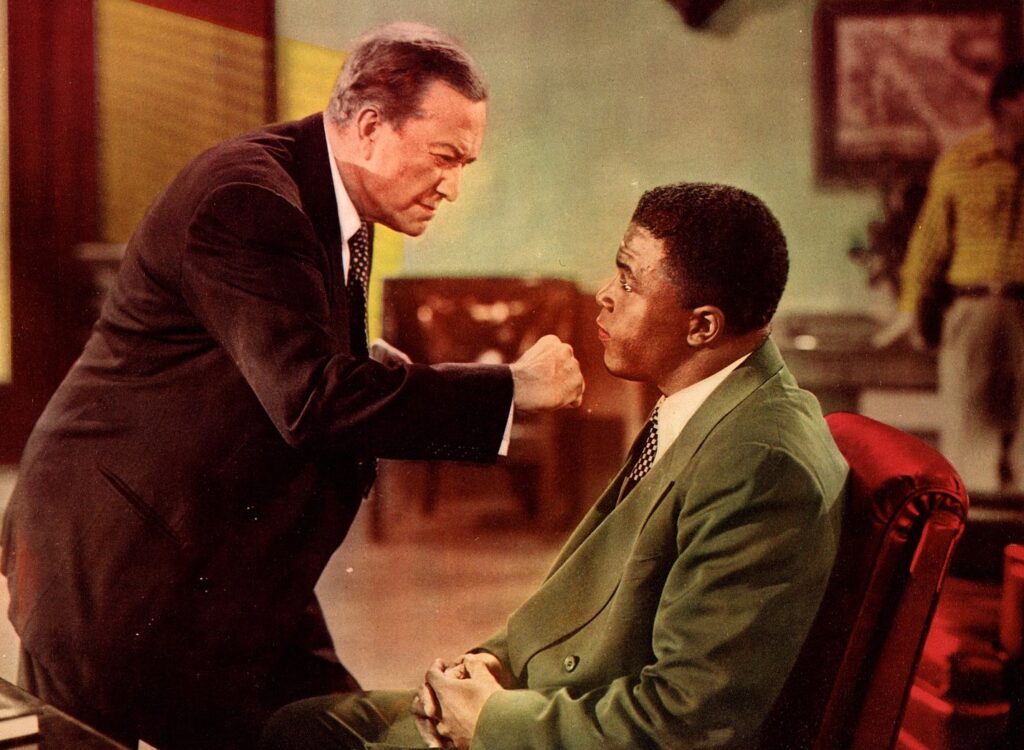

From The Jackie Robinson Story

Source: Public Domain

McKinsey & Company, the famous management consulting firm, has published a number of wildly popular reports during the Great Awokening—such as 2015’s “Diversity Matters,” 2018’s “Delivering Through Diversity,” 2020’s “Diversity Wins,” and 2023’s “Diversity Matters Even More”—asserting that gender and ethnic diversity in corporate management is a magic bullet for making money.

McKinsey is a (highly) for-profit entity not otherwise known for doing disinterested scientific research just to advance the frontiers of knowledge. Then again, neither is McKinsey an investor trying to pick undervalued stocks. Instead, it makes its money telling the C-suite what the bosses want to hear.

But all that didn’t induce much news media skepticism about McKinsey’s reports…until recently as DEI has slightly receded in fashion.

Now, however, the conservative press is finally starting to publicize the old doubts of the business school researchers who live to find ways to outsmart the stock market.

For a summary of why the greatest concentration of outspoken skeptics about McKinsey’s epochal discoveries have been concentrated in B-School faculties, see London Business School professor of finance Alex Edmans’ blog May Contain Lies. Here are some highlights of his critique of McKinsey’s latest:

The paper is remarkably non-transparent about its methodology. The body of the paper never describes the sample of firms included in the study, what their dependent and independent variables are, and so on. This may be to stop people replicating their study as their prior research was found to be irreplicable. It is as if they hope that people will accept the results because they want them to be true, and not ask any questions (again, the opposite of diversity of thought).

The single most fundamental rule of thumb for thinking about causality is that X couldn’t likely have caused Y if Y happened before X. But not in McKinsey’s world:

But the McKinsey study makes an even more basic error absent from the other studies: they measure diversity after they measure financial performance! In their own words, “The analysis of this report is based on 2022 data on diversity in leadership teams and 2017-2021 data on financial performance.”

To draw a baseball analogy, were the Los Angeles Dodgers the highest-revenue franchise from 2017 to 2021 because in the 2023–2024 offseason they invested over $1 billion dollars in two Japanese stars, Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto? Or is Los Angeles already being the richest franchise why Dodgers were, as expected, able to afford the top two Japanese players? (Japanese players are more expensive for American teams than, say, comparable Dominican players: The Dodgers had to pay a $50 million fee to Yamamoto’s Japanese club for the right to pay him $325 million over 12 years.)

The answer to the baseball question is obvious, but then we tend to think more clearly about sport than about society. Edmans observes:

This makes it very likely that any relationship is due to reverse causality: it is financial performance that allows companies to invest in diversity, rather than diversity causing financial performance. (Indeed, my own work finds that financial strength is associated with superior future diversity, equity, and inclusion).

Competent executives and board members who check the currently preferred sex and race boxes are much in demand these days. High-quality People of Diversity are a luxury item more affordable by profitable corporations (and low-quality PoDs are less of a risk to strong firms to drive them into bankruptcy).

Also, McKinsey reports only one measure of profitability, Earnings Before Income and Taxes:

McKinsey’s earlier results were earlier shown to be untrue for all of these alternative profitability measures, leading to concerns about cherry picking the one measure that worked.

And why not report what really matters?

Moreover, it is not clear whether you should be measuring profitability at all. The most relevant performance is (long-term) Total Shareholder Return. TSR is what investors actually receive. TSR is far more comprehensive than EBIT (or any profitability measure). If a company announces a new patent or wins a big customer contract, it will boost the stock price but not immediately lift EBIT. More importantly, TSR is forward looking. Many tech companies have enjoyed soaring TSR despite modest profits due to their long-term potential.

Tech companies have of course driven much of the growth of stock indices over recent generations. (Six of the top seven firms on earth in market capitalization at the beginning of this month are American tech companies.)

If Asians like Jensen Huang of Nvidia, the graphics processing unit chipmaker that is the third most valuable publicly traded firm in the world, are redefined as white-adjacent, then the founders of tech companies are notoriously nondiverse. A legendary Silicon Valley investor once told me he’d analyzed the founding teams of over 150 “unicorn” start-ups with valuations of at least one billion dollars. Only three had female founders, and they were part of husband-wife pairs.

So, McKinsey’s choice to report profitability rather than stock performance biases their results.

You might have wondered why, if McKinsey had actually discovered a major, enduring, and well-publicized violation of the notorious Efficient-Market Hypothesis (that it’s tough to consistently beat the stock market using public information), why day traders weren’t sitting at home counting pictures of corporate officers and board members by demographic categories, and getting rich by betting on the more diverse firms.

Note that you don’t have to believe in the Efficient-Market Hypothesis, which has been around more or less since finance economist Eugene Fama’s 1970 paper, but you very much ought to consider it when thinking about how to invest.

Consider that back in the 1970s, mutual funds typically charged an 8 percent “load” so you could compensate E.F. Hutton for talking when others listened or, more justifiably, subsidize Smith Barney’s wonderful John Houseman Paper Chase character commercials.

Of course, practically no stock picker ever beat the stock market by enough to make these funds worth the 8 percent load. If they were that good, why would they even cut you in on their lucre? (Indeed, one hedge fund that does have a track record of drubbing the market over three decades, James Simon’s Renaissance Technologies, is largely run for the benefit of the math geniuses who work for it.)

Hence, today, the most popular investment funds tend to resemble those offered by Vanguard, which has $7.7 trillion under management because it focuses on minimizing the fees it charges its clients by simply reproducing the S&P or the like. Why spend money on putative financial seers when you can exploit the wisdom of the crowd for very little? (Of course, if everyone followed Vanguard’s strategy of freeloading on those trying to beat the market, asset prices would become badly wrong because nobody would still be doing the hard work.)

Obviously, lots of rich guys have outperformed the market. But the lengths they need to go to try to outgun the efficient-market hypothesis are pretty impressive. For example, in the 1983 Eddie Murphy nature vs. nurture comedy Trading Places, Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche try to beat the orange juice futures market by stealing a Department of Agriculture forecast of the orange harvest. But already by that point, the most successful commodity traders in cocoa futures were employing a network of bush pilots to aerial photograph the immense African hinterland to see how this year’s cocoa harvest was coming.

Or high-speed traders will engage in prodigies of investment to shave milliseconds off the time it takes to arbitrage markets in Chicago and New York.

In contrast, anybody could have sat in his pajamas and counted the diversity of publicly traded firms’ leadership and invested in the most diverse ones. Yet, I’ve seldom heard of anybody trying to beat the market by doing it.

It’s almost as if people tend to believe our orthodox cant about diversity with the part of their brain devoted to being socially acceptable, yet simultaneously disbelieve it with another part dedicated to making money.

Similarly, I’ve seldom if ever heard anybody argue that diversity is more valuable in one type of industry than another, even though that’s more reasonable-sounding than that diversity is a panacea.

For example, it’s not implausible that women executives and board members would tend to be beneficial at Lululemon (although the yoga pants retailer was founded by billionaire Chip Wilson, an Ayn Rand-worshipping, DEI-despising straight dude with studied opinions on women’s butts).

But that logic would conversely suggest that male leadership would be better at Nvidia, whose chips power such male-dominated activities as gaming, cryptocurrency mining, and artificial intelligence. Of course, diversity-mongers are desperate to sink their claws deeper into Nvidia, so you aren’t going to hear that. Instead, diversity will continue to be hawked, no matter how implausibly, as a universal cure-all.

There are well-known stories of firms getting a leg up on rivals by discriminating less. The most famous might be the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 1946, the most distinguished baseball executive, Branch Rickey, broke the long ban on black ballplayers by signing Jackie Robinson. Brooklyn then stayed out ahead of most other clubs by playing ever more blacks. In return, during Robinson’s ten-year career (1947–1956), black Dodgers were five times the National League’s most valuable player and four times the rookie of the year. The Dodgers won six league championships and lost two others in the last inning of the season.

What about firms that started hiring more women around 1970? Surely, some firms quickly got a leg up because there were plenty of competent women who were underemployed before social norms changed abruptly about a half decade after the end of the baby boom. But, to my frustration (I like being aware of historical examples), I can’t name any companies that flourished by hiring and promoting more women.

I suspect this is partly because customs changed faster and more universally regarding women than blacks. In contrast, the St. Louis Cardinals and Boston Red Sox met in the 1946 World Series but never made it back during the subsequent prodigious careers of Stan Musial and Ted Williams, respectively, due in part to their managements not integrating for a decade or more after Brooklyn had.

But it’s also because our dominant mindset is averse to recollecting that corporations have obvious financial incentives to not discriminate irrationally. Recounting how quickly American culture switched to encouraging women and blacks a half century ago would undermine the conventional wisdom that they are still pervasively undermined by systemic racism and sexism.