March 20, 2014

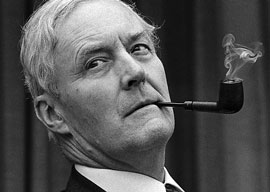

Tony Benn

Last week saw the passing of two prominent figures on the extreme left wing of British politics: Tony Benn and Bob Crow. Politicians of all persuasions have made the inevitable polite tributes to their memory. They were remarkable men.

Crow was a key figure in the trade union movement, a radical fighter for the rights of the members of his Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers” Union. Those not from Britain would most likely have come across the effects of his leadership were they to have traveled to London during one of the repeated Tube strikes that he orchestrated.

Tony Benn represented a different type of extremist within left-wing politics. From a respected political family, he successfully fought to renounce the hereditary title that had been awarded to his father, the 1st Viscount Stansgate, and that prevented his sitting as a Member of Parliament in the House of Commons. He served under Harold Wilson in the 1960s, serving as Postmaster General and then in the cabinet as Minister of Technology, before returning to office as Industry and then Energy Secretary in the 1970s.

Crow died aged 52 of a heart attack at the height of his career; Benn was 88, having retired as an MP in 2001 (in his own words, “leaving parliament in order to spend more time on politics”) to become a grand old man of British politics and one of his generation’s great political diarists. Class warriors determined to fight battles that most people in the country would have said belonged to conflicts that had ended decades ago, they probably caused more embarrassment and difficulties in their careers for Labour politicians than they ever did for their Conservative opponents. Both were men of real intelligence who never managed to see that the attacks on industry that they so supported had in the long run done more damage to their support base than any of the short-term victories that they achieved. Benn’s extremism developed as his career progressed (Wilson, exasperated, complained of him as a man of “tomfool issues, barmy ideas, a sort of aging, perennial youth who immatures with age”); Crow was out there on the edge from the start. The difference is perhaps not surprising, given their respective backgrounds: the private school- and Oxford-educated heir of a left-Liberal political family and the state-educated working-class boy who left school at sixteen to join London Transport.

Benn was of endless benefit to Margaret Thatcher’s election victories, and Crow probably won more votes for the Conservatives in London than for Labour. He certainly helped Boris Johnson’s reelection. (Johnson actively linked his opponent, Ken Livingstone, with Crow in his campaign.) Neither was deterred by their remarkable usefulness to the right and the rejection of their policies by the majority of the electorate. It is very, although by no means uniquely, British that people have lamented their passing most of all because of the single-minded form of integrity that they found so discordant when they were alive. To a degree they may well be right to miss that; after all, it is an increasingly rare commodity. That doesn”t mean that men of integrity are always helpful, consistent (it was said of Benn that he “had more conversions on the road to Damascus than a Syrian long-distance lorry driver”), or even right (as H. L. Mencken memorably quipped: “An idealist is one who, on noticing that a rose smells better than a cabbage, concludes that it makes a better soup”). But in an age where so many political agendas seem to consist only of the determination to achieve reelection, one can understand why the loss of two uncompromising idealists might be regretted.

Idealism tends to be an indulgence most attractive to and, crucially, most to be desired in the outsider. The list of human disasters caused, often very deliberately, by idealistic leaders is extensive. Idealists are dangerous: Even in ancient Rome, Cicero criticized the disruptive attitude of the elder Cato, noting, “For he gives his opinion as if he were in Plato’s Republic, not in Romulus’s cesspool.” That a man as widely loathed in his life as Crow was by so many Londoners might, after his death, be seen as a lamented man of principle by those same people, says much about death and the human condition, as well as about the man himself. But it also reveals something less positive about how politics are perceived here and much more broadly in Western democracies.

As it happens, I strongly believe that the vast majority of politicians in Britain began their careers because of a vocation to which they remain true and hold principles that are probably stronger than those of the majority of their peers. But every loft has its bad apples, and the necessary denunciations of those few who have fallen have undoubtedly done much to cast suspicion on the motives of the largely blameless remainder. It is the wrong note that is most jarring in a symphony and that one later remembers. That is not to say that the media spotlight on politics that has increased so exponentially since Watergate and, in Britain, Profumo, is to blame for our cynicism. One only has to read Trollope’s novels or look at Gilray’s cartoons to see that. Cynicism has always been there in the electorate and is often the most important tool we have in the resolution of the oldest of all political problems: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?