November 04, 2014

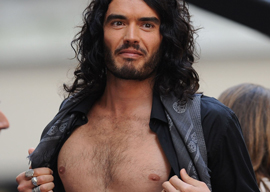

Russel Brand

Source: Shutterstock

What do you call a socialist who tries to make money selling books? The answer isn”t just Noam Chomsky; it’s every socialist who walks the earth. The soothsayers of post-scarcity love to criticize the profit motive while trying to make a living by putting words on pages. Like Marx suckling off the gains of Engel’s cotton mill, they live off the generosity”or dim-wittedness”of others.

Russell Brand, the loud-mouthed, drug-addled actor and comedian of British descent, is the latest socialist provocateur to write a book calling for upheaval. Ever heard of Brand? Perhaps you have seen his gratuitous antics in movies like Get Him to the Greek. If not, you didn”t miss much. As far as I can tell, Brand is the same in real life as in fiction: lewd, obnoxious, and inane. His attempts at comedy are no better. From the little stand-up I”ve watched, Brand repeats dirty words at increasingly high decibels to turn shock value into laughter. He’s the type of humorist a middle-school boy raised by an absent-minded single mother would find hysterical.

So how does Brand’s new book, Revolution, fare in comparison to his other crafts? I”d rather chew glass than read his manifesto on political change, so instead I”ll rely on what dumb people quote to sound intelligent: book reviews.

The Guardian recently assembled a panel of young writers to review Brand’s work, probing to find if idealistic millennials would be struck by the call to arms. The answer was, shockingly, yes; young minds are always itching to change the world. And as a general rule, when millennials find something inspiring, it’s probably awful.

The majority of the youthful writers agree on one thing: what Brand lacks in substance he makes up for in awareness. Journalist and “social activist” Vonny Moyes assures us there is more to Brand’s masterpiece than a “narcissism trip.” He is “opening a dialogue we all need to be having.”

And what, exactly, is that? In American terms, Brand is your typical petulant Democrat, crying over the specter of inequality and the small people lacking a voice. He wants to toss off the chains of the corporate-government duopoly through non-voting, profit abolition, and debt cancellation. In doing so, Brand hopes to shake up the political establishment and decentralize things away from the power brokers and kingmakers. He writes, “I know most people want change. I know most people can”t be happy with the current regime.”

That’s a sentiment anyone fed up with politics can agree on. It doesn”t take a doctorate in philosophy to know the political system is geared against the little guy. Since the advent of the nation-state, the machinations of government have been used to corral society under the thumb of a few shrewd men. Brand seems to think he’s tossing the curtain off of Oz by pointing out this fact. He fancies himself a revolutionary trailblazer in thought, going as far as to question the very nature of reality and what it means for the modern lifestyle.

Here’s something Brand and his legions of cookie-cutter idealists forget: the average person doesn”t care very much for revolution. Soapbox sermons on the collective power of democratic masses make eyes roll, not widen with optimism. If Brand really thinks he’s the one to lead a revolution, I have a bridge to sell him in Pennsylvania Amish country.

With few exceptions, normal people don”t long for a perfectly equitable future. They know the government is a predatory institution that, on occasion, fixes the pothole in front of their house and locks up murdering fanatics. These basic functions keep the political class safe from the pitchforks. It’s why Brand’s empty proselytizing will never catch on outside of a few hippie circles on college campuses. The working class is too busy making ends meet and raising families. They don”t have time for an earthly utopia.

Thankfully, no thoughtful political commentator is taking the Russell Brand revolution seriously, either. Journalists who cover public affairs are often enamored of lofty rhetoric and convoluted promises. Brand’s romantic ego trip sounds like the type of thing lefty columnists would lap up, similar to when they diligently read excerpts of Das Kapital in their dorm rooms.