December 04, 2011

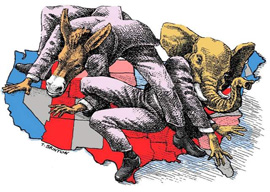

In the December issue of The American Conservative, Gary L. Gregg defends the Electoral College as an integral part of the “Founders’ design.”

Gregg goes after the proponents of the National Popular Vote plan, a group accused of trying to nationalize presidential elections. He says they have carried out a “stealthy and disciplined state-by-state campaign” to undo a wise safeguard against hell breaking loose, and they have thus far won approval for their plan in eight states and the District with the aid of 2,100 presumably misguided state legislators. It’s not entirely clear what’s “stealthy” about a plan that lots of state legislatures are already earnestly debating.

Gregg has a thing for the now-threatened Twelfth Amendment, which was passed in 1804 to deal with the “problematic election” of Thomas Jefferson in 1800. This problem first erupted with the disputed election of John Adams in 1796. It was then that the original electoral plan in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution came under fire. Under this plan, electors from every state cast two votes for president, and the candidate with the second-highest total was awarded the vice-presidency. Under deadlocks, the election was turned over to the House. Rivals for the presidency—some of whom such as Adams and Jefferson hated each other’s guts—could and did hold the #1 and #2 spots in the executive branch. The Twelfth Amendment, which Gregg praises to the skies, awarded state electors only one vote and required the candidates for president and vice president to run separately. It arranged for a more expeditious settlement of deadlocks which had to be handed over to the House of Representatives for a final judgment. In time vice-presidential candidates ceased to run separately because the two national parties started running vice-presidential and presidential nominees on the same ticket.

Gregg maintains that the Electoral College provided for a balance between “competing values” at stake in creating the president’s office. The college is based on “recognition that the people and their communities are the ultimate source of power,” but it “encourages the president to be sufficiently independent so that he could act his part with vigor and resolve.”

Gregg’s defense doesn’t speak to me—or, as the Germans would put it, it “couldn’t lure a dog behind the oven heat.” The Amendment harkens back to another society, one which approached elections very differently than we do. In 1789 electors were selected by state legislatures in seven out of thirteen states. It was entirely up to the state assemblies to decide how the electors were picked. This remained the case until many decades after the founding. Until the federal government began taking control of the situation after the Civil War, voting usually excluded women, vagrants, and sometimes people of color.

Defending the Electoral College as it now functions is not the same as upholding the principle of ordered liberty as understood in 1789. Like Madison and Hamilton, one can certainly be for limited government, dual sovereignty, and balance of power without having to defend a system of organizing presidential elections that in no way addresses such modern problems as an overly centralized executive regime and two privileged national parties that monopolize presidential races.

Gregg imagines that the two-party monopoly leads to moderation, and he views the EC as a necessary means to avoid having “the most extreme elements of each party empowered.” Further: “Without the moderating system [furnished by the duopoly in American politics], the extremes of each party would be empowered to blackmail more prudent candidates.”

Indeed we should rejoice over these government-sponsored two parties. If we didn’t have a system that “exaggerates” each major party’s victory, we’d be in a real pickle: “Our politics would be moved out of the center,” a situation that, we are warned, would create chaos. Our elections would degenerate into a “Jamaican limbo dance,” with eccentric figures like Ross Perot popping up all over the presidential landscape. (I’ve no idea what a Jamaican limbo dance is, but I’m sure it’s something quite nasty.)

In Gregg’s nightmare scenario, absent the Electoral College our politics would be shifted from the center in ways that would radicalize “the Democratic Party, as the path to the presidency became one where smaller states and rural areas could be ignored with impunity.” Have I been looking at the wrong political landscape? Does President Obama represent the “center” that the Electoral College is keeping alive? The “center” has been moving leftward since I was a kid in the 1950s. It’s silly to pretend that the two-party monopoly has encased us in a permanent centrist cocoon between two evil extremes. We’ve obviously moved away from what used to be the center—mostly toward the left.