June 23, 2021

Jane Austen

It’s widely assumed today that, due to systemic sexism, women were so culturally oppressed until roughly last week that, of course, there were few famous women writers.

In truth, however, women have made up a sizable fraction of professional novelists for centuries. But why then aren’t these old-time women writers more renowned today among anybody not trying to get tenure?

For example, in the comments at Scott Alexander’s Substack for smart nerds, one commenter, irate that sixteen of the seventeen reviews that Scott had published by his readers were of books authored by men, scoffed:

So you discount the structural forces that lead to vastly more men than women appearing on our proverbial bookshelves?

But, of course, if you look at actual bookshelves, a large fraction of books are written by women. And it’s been that way for a long time.

One obvious reason that readers of a website that grew out of the Rationalist cult are more likely to be interested in books by men than by women is that nerds don’t much like fiction, especially fiction about people and their relationships. They’re Rationalists, not Emotionalists! So, all the books reviewed were nonfiction.

The novels of men and women aren’t hugely different, but a computer that has studied 67 million words of fiction can guess the sex of the author with 72 percent accuracy.

In the study, Dr Luoto says that compared with straight men, women used more social words, personal pronouns, positive emotion words and words related to sadness and anxiety. “Heterosexual men, by contrast, used more articles, numbers, spatial words, death and anger-related words, swear words, and words that reflect analytical thinking.”

Women have been highly successful fiction writers for several centuries.

By way of illustration, consider how colossally influential was Daniel Defoe’s 1719 adventure novel Robinson Crusoe, which inaugurated its own genre of shipwreck fiction, Robinsonade, as reflected in Swiss Family Robinson, Lord of the Flies, and The Martian. Yet, Defoe’s book went through fewer printings in the 18th century than Elizabeth Singer Rowe’s 1728 work of epistolary fiction, Friendship in Death, in Twenty Letters From the Dead to the Living.

In James Boswell’s famous 1791 biography The Life of Samuel Johnson, the critic Dr. Johnson is always complaining about how much money lady novelists make, but then confessing that he had just stayed up all night reading the latest page-turner by a woman writer. (Dr. Johnson and Edmund Burke were frequent guests at the Bluestockings salon organized by wealthy women literary intellectuals.) But people still occasionally read Boswell (just open his Life at random and see if you find it amusing), although virtually no books by women written before Jane Austen (1775–1817) are read.

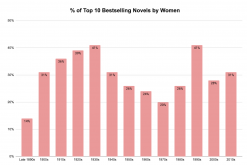

We can graph the percentage of women on the Publisher’s Weekly annual list of the top ten best-selling novels in the U.S. from 1895 onward:

It’s striking that there were more top-of-the-charts women novelists in the first four decades of the 20th century than in more recent times. (Note that for some reason, Harry Potter books were excluded from these lists, depressing the 2000s’ female percentage.)

For example, the top-selling novel of 1900 was Mary Johnston’s To Have and to Hold:

‘To Have and to Hold’ is the story of an English soldier, Ralph Percy, turned Virginian explorer in colonial Jamestown. Ralph buys a wife for himself—a girl named Jocelyn Leigh—little knowing that she is the escaping ward of King James I, fleeing a forced marriage to Lord Carnal…. Lord Carnal attempts to kidnap Jocelyn several times…. The boat they are in, however, crashes on a desert island, but they are accosted by pirates, who, after a short struggle, agree to take Ralph as their captain…

And then a whole bunch of other stuff happens…

A few of the best-selling women writers of the early 20th century are still read today, most notably Edith Wharton.

But in general, all but a few well-paid authors, male or female, will fade into obscurity. For instance, perhaps the dominant commercial author of the first decade of the last century was a young American naval officer–turned–historical novelist named Winston Churchill.

Oddly, this Winston Churchill was not the future prime minister, a former British army officer who wrote only one novel. To lessen public confusion, the two Churchills came to an agreement that the more famous American would remain “Winston Churchill” while the Englishman would publish under the name “Winston S. Churchill.”

Why did women novelists fall in popularity from the 1940s through the 1970s? There are no doubt many reasons, but an important one that has been almost completely forgotten because it doesn’t fit into Woke mythologizing of the past is that the bohemian artists who would become the cultural elite of mid-century America turned sharply against bluestocking feminism after its year of triumph, 1919, when women were given both Suffrage and Prohibition.

Wilfrid Sheed wrote of the mid-century New Yorker:

Thurber’s world cannot remotely be understood without understanding Prohibition, or the locker-room version of it: a plot brewed up by women and Protestant ministers while our soldiers were overseas, in order to end America’s men-only culture and bring the boys all the way home, not just as far as the nearest saloon.

Prohibition was the mistake that made feminism uncool until 1969.

When feminism came back a half century ago, there was much academic emphasis on rediscovering lost books by female writers. But…they turned out largely to be best-sellers, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and (until race came to rule over all) Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (which, by the way, is an outstanding read).

There weren’t really many esoteric art books by ignored women novelists to be rediscovered by feminist scholars. The small number of avant-garde female stylists were already famous: e.g., Elizabeth Taylor won the 1966 Best Actress Oscar for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Charles Murray’s 2003 book Human Accomplishment compiles objective rankings of the most eminent individuals ever in the arts and sciences by counting how many times they are mentioned in leading reference works. Women make up only 2 percent of the eminences.

Is this a fair methodology? Mostly. Scholars need to create plausible narratives of who influenced whom, so they must base their opinions largely on those of their subjects. For example, Brahms was awestruck by Beethoven, so, yes, Beethoven really is good, just like he sounds.

But this approach may be somewhat unfair to female artists because they are less likely to have genius followers. For instance, poet Ezra Pound outranks novelist Jane Austen in Human Accomplishment, in part because Pound employed Ernest Hemingway and edited T.S. Eliot, so his name comes up whenever the history of literary modernism is recounted. In contrast, Jane Austen’s indisputability as the greatest woman writer of all time on the subject of husband-hunting works against her fitting into a satisfying narrative of influence. Pound benefits from Hemingway and Eliot being better than him, while it’s all downhill after Pride and Prejudice.

In general, men tend to be more interested than women in greatness. You’ll notice that guys are always making up top ten lists. In contrast, how often do women get into arguments about who was the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time)? Women tend to want to be better than other women around them, but they seldom see themselves as competing with the dead greats.

This sex divergence is partly because men are more interested in personally irrelevant stuff than women are, but it’s also because men have bigger top-of-the-pyramid payoffs than women do: Genghis Khan (who ranks way up there on my top ten list of contenders for the GOAT of conquerors) fathered a lot more children than any woman ever gave birth to.

Also, men tend to be more nostalgic and loyal to their old favorites and thus keep their heroes’ names alive, while women tend to be more interested in new fashions.

This raises questions about Disney’s strategy with their Star Wars property to assume that its male audience will always remain loyal, just because every guy remembers when he first saw Star Wars (for me, a 10 a.m. showing in May 1977), but they can recruit the female Harry Potter audience by going Woke.

But is Star Wars really the hot new thing that the female sex wants to associate themselves with?

And is anybody inside Disney allowed to even ask that question these days?