July 06, 2016

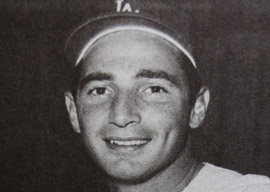

Sanford Koufax

“Three thousand years of beautiful tradition, from Moses to Sandy Koufax, you”re goddamn right I”m living in the f—-ing past!”

“Walter Sobchak in the Coen brothers” The Big Lebowski

This is the 50th anniversary of pitcher Sandy Koufax’s final season in baseball, in which he walked away at age 30 after his 27″9 won-loss record carried the Los Angeles Dodgers to their third World Series in four years.

With a half century of perspective, I think I can finally make sense of some of the facets of the Koufax conundrum.

Was he really that good? How did he become so overpowering? And why was he so famous?

He certainly was famous, especially to a 7-year-old in Los Angeles. My 1966 Sandy Koufax Topps card was the pride of my baseball-card collection. The rumor among the other kids on my block was that Koufax lived in the mysterious house on the corner. (He didn”t.)

To this day, Koufax remains the most legendary Jewish athlete since Samson.

The Coen brothers likely were fans of the Minnesota Twins, who were Koufax’s opponents in the 1965 World Series. Koufax had been scheduled to pitch the first, fourth, and (if needed) seventh games against the Twins, allowing him the then-usual three days” rest between starts. But he asked fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Don Drysdale to take his place in game 1 because it fell on Yom Kippur.

Koufax was a worldly man (he owned the Tropicana Motel in West Hollywood, the center of the rock & roll business, where Jim Morrison of the Doors lived for three years), but honoring his religion struck him as the right thing to do. Koufax, never an articulate speaker, didn”t much explain his decision, but his taciturnity was appealing in its cowboy-movie “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do” fatalism.

Drysdale, unfortunately, was shelled. He joked to manager Walt Alston, who came to take him out in the third inning, “I bet right now you wish I was Jewish, too.” Then Koufax lost the second game, putting the Dodgers in a deep hole.

Los Angeles rallied, however, with Claude Osteen, Drysdale, and Koufax winning the next three. When Osteen lost the sixth game, however, Alston had to choose between Drysdale on three days” rest and Koufax on two.

He called on Koufax. Sandy found his arm too tired to throw his ferocious curveball, but managed to rely on his famous sailing fastball for a three-hitter to win 2″0. It was the ultimate display of Koufax’s strength-against-strength style, with his disdain for guile.

Admittedly, if Jim Gilliam hadn”t made a great defensive play in the fifth inning, Koufax might have lost the seventh game, and a hundred thousand bar mitzvah speeches would have needed a different illustration. But there was nothing foreordained about Koufax’s ultimate triumph, which only made his taking the risk more heroic.

Even as he enters his ninth decade, Koufax may remain the most intriguing of all Jewish celebrities to his fellow Jews. For example, President Obama threw a party at the White House in 2010 to recognize Jewish-American Heritage Month. There was no shortage of famous Jews in attendance, but even the billionaires, senators, and movie stars were agog that they were in the same room as the seemingly reclusive Koufax.

In truth, he’s not a J.D. Salinger-like eccentric; he just prefers a normal life out of the media spotlight.

Another part of Koufax’s appeal to Jews has been his intensely Jewish good looks. A half decade ago, I went to see a documentary movie about Wall Street at an Encino art-house cinema with a mostly Jewish audience. A trailer was shown for a documentary called Jews and Baseball: An American Love Story. When Koufax, then in his mid-70s but wearing a great suit and looking as dapper as ever, appeared on screen for an interview, the middle-aged Jewish ladies in the crowd gasped in delight.

Koufax was certainly a good baseball player as well. During his last four years, he averaged 24 wins and 7 losses per season.

These seem like numbers from some lost epic age. By way of comparison, the Dodgers” current superstar pitcher, Clayton Kershaw (whom 88-year-old Dodger announcer Vin Scully, in a rare and forgivable slip, recently referred to as “Sandy Koufax”), had a record of 18 and 7 over his best four-year stretch.

(Here’s Scully calling Koufax’s 1965 perfect game and Kershaw’s 2014 no-hitter.)

But Kershaw plays in an age that conserves pitching talent more prudently. Kershaw starts every fifth day, while Koufax pitched every fourth. In his 2014 Most Valuable Player season, Kershaw completed six games, a career high. Koufax threw 27 complete games in each of his last two years.

Sandy had to soak his left arm in an ice bucket after each game from 1962 to 1966, when he said to hell with it. (Similarly, Drysdale, who threw 300 innings per year from 1962 through 1965, was done at age 32 in 1969.) In retrospect, it would have made more sense for management to baby Koufax the way the recent fragile pitching genius Pedro Martinez had his career extended through restrictions on the number of pitches that he was allowed to throw.

Kershaw is a more skilled craftsman than Koufax, who was a blunt-force trauma pitcher, throwing only two pitches, a rising fastball and a huge curve.

Koufax had been a teen prodigy, signing a bonus contract that, under the rules of the time intended to lessen competition among owners, prevented him from being sent to the minor leagues to get the experience he needed. As a 19-year-old, Koufax threw two shutouts in five starts for the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers. But through 1960 Koufax was still only 36″40 for his career, while the younger but wilier Drysdale had established himself by age 20 as an ace.

Catcher Norm Sherry suggested to Koufax that if he didn”t try to strike out every batter, he”d walk fewer. This rather simple idea apparently came as a revelation to Koufax, who went a fine 18″13 in 1961, his seventh season. When the team moved into capacious Dodger Stadium in 1962, Koufax’s soaring fastballs stopped being hit out of the park. When the strike zone was expanded vertically in 1963, Koufax’s combination of high heat and plummeting curves became overwhelming.

One reason the New York-born Koufax was so renowned was that he and his Los Angeles-born teammate Drysdale epitomized the golden age of the Golden State. Baseball statistics analyst Bill James once wrote a book complaining about the worst choices in the Hall of Fame, and concluded that the two least deserving postwar players were Drysdale and New York Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto. James alleged that Rizzuto is in because Manhattan circa 1950 was such a halcyon time and place that its local heroes, such as Rizzuto and Broadway star Marlon Brando, remain overrated by the press.

But much the same was true of Los Angeles in 1962, when Drysdale went 25″9. The two great monuments of Los Angeles Modernism, Dodger Stadium and LAX, opened in 1961″62, when the Beach Boys had their first hits.

It’s all been downhill since.

It also didn”t hurt that in retirement both marginal Hall of Famers became popular announcers, Rizzuto a lovable eccentric, Drysdale a polished professional. Koufax, on the other hand, signed a million-dollar contract with NBC’s Game of the Week, but quit after two years because he didn”t much like talking.