September 07, 2022

Mississippi State Capitol

Source: BIgstock

Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, didn’t have running water last week. Fortunately, water pressure has now been restored, but the unhappy residents are still being instructed to boil their tap water.

The Washington Post explains that the reason 82.5 percent black Jackson can’t keep its water running is…white people. Specifically, white people who aren’t around anymore:

White then Black residents abandoned Jackson, propelling its water crisis

Jackson’s travail is

…rooted in decades of racism, historians and infrastructure experts say…. White flight beginning in the 1970s drove onetime Jackson residents into neighboring areas.

But the black takeover of the state capital didn’t create Wakanda.

Luckett said the city’s infrastructure problems started around 1970, when federal courts forced Jackson schools to desegregate—16 years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. Thousands of White families moved out of the city, many sending their children to private schools run by the White Citizens’ Councils, white supremacist groups, he said.

White supremacists! You can’t live with them, you can’t live without them:

The city’s decline since then has prompted better-off Black residents to escape Jackson’s failing infrastructure, not just water but also roads and schools.

As the middle class, white and black, flees, the remaining residents of Jackson are increasingly made up of the dregs of society. The city appears to have had the worst homicide rate of any of the 200 biggest cities in 2021, at 90 killings per 100,000 people, twice as bad as Detroit. As I wrote in this column last January:

At that rate, a black man trying to live out his three score and ten years in Jackson has well over a 10 percent chance of having his life end violently. Not surprisingly, the population of Jackson is now only three-fourths of what it was in 1980.

Jackson’s downfall appears to be accelerating as even the number of blacks declined in Jackson from the 2010 to 2020 Census. Its overall population was down 17 percent from 2000 to 2020, and the new decade’s water and murder crises can’t be doing much to stop the bleeding.

But a crucial point to note is that there’s nothing unique about how black-run Jackson is depopulating. The same process is happening in quite a few other black-dominated cities.

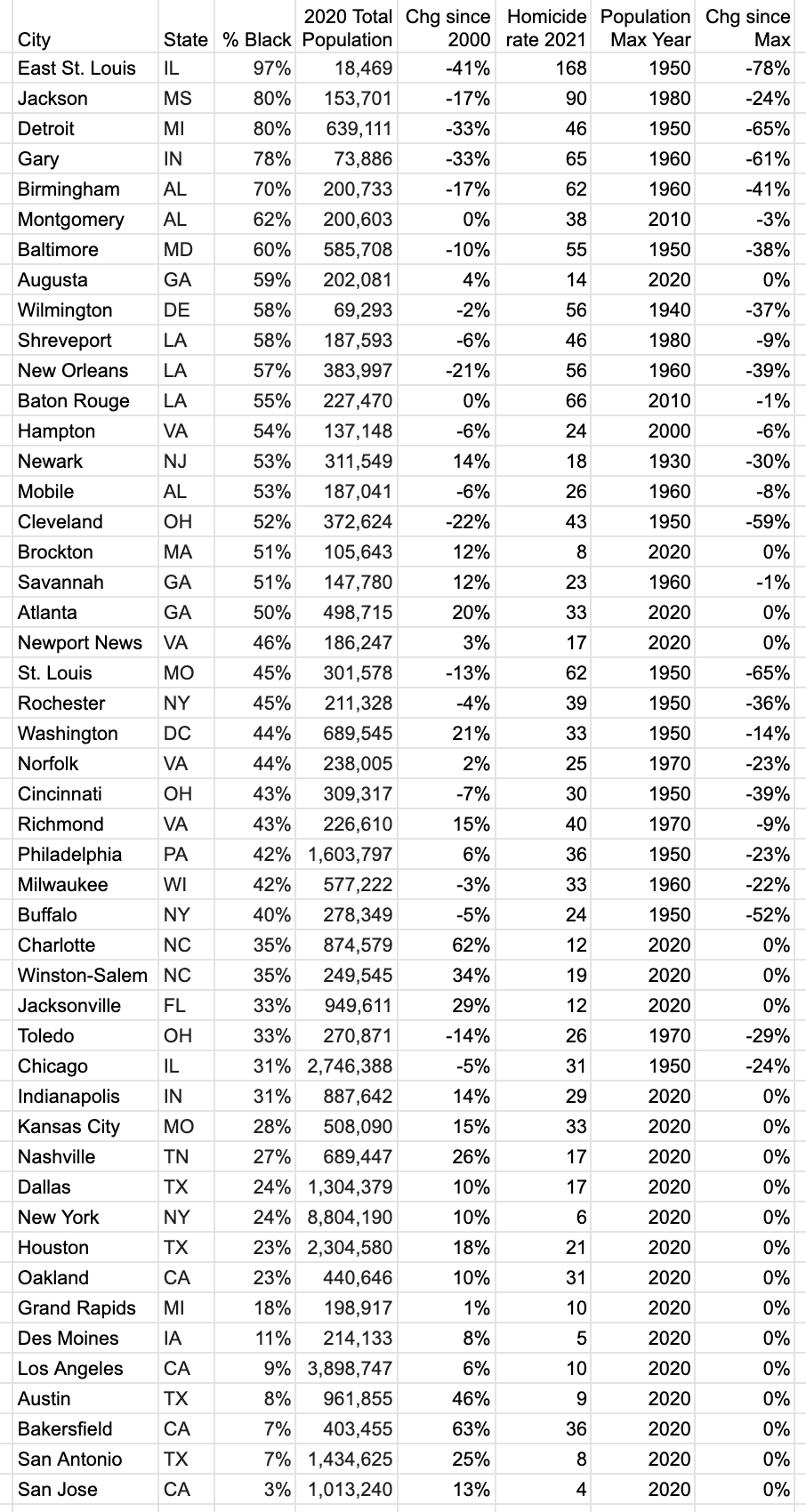

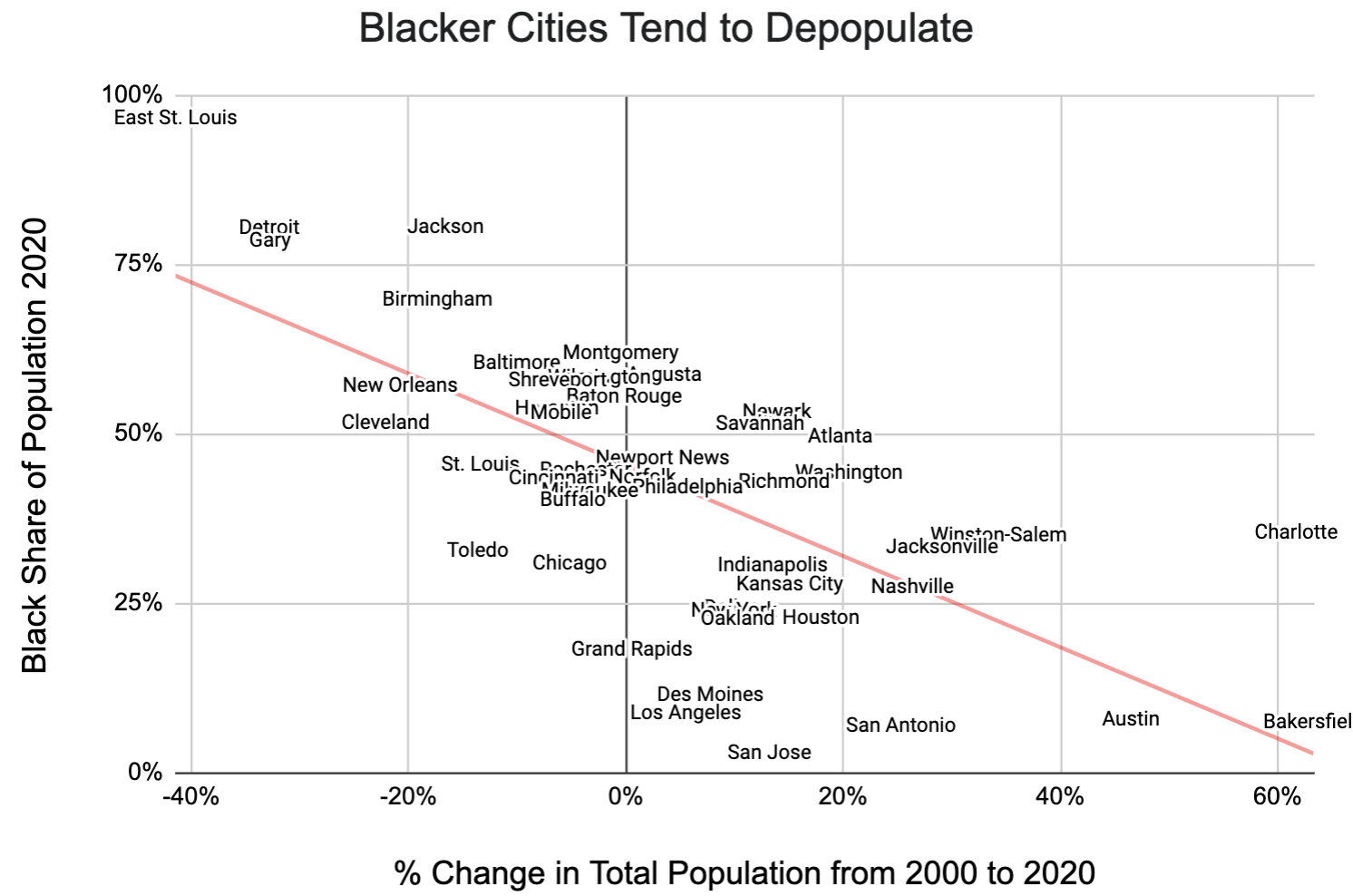

I pulled together a list of 48 American cities (see the bottom of the article for my data table) and created a scatter plot showing their black share of the population on the vertical axis and their change in total population from 2000 to 2020 on the horizontal axis:

The five blackest cities on my list—East St. Louis, Ill.; Jackson, Miss.; Detroit, Mich.; Gary, Ind.; and Birmingham, Ala.—have all lost at least one-sixth of their population over the past two decades.

Across the 48 cities, there’s a moderately consistent relationship between population change over 2000–2020 and 2020 black share of the population, with a fairly strong correlation coefficient of r = –0.68. Similarly, the correlation between population change and the 2021 homicide rate is r = –0.59.

Admittedly, I can’t guarantee that my sample of 48 municipalities, which includes most of the heavily black cities in the country, is totally representative. After a while, I got bored looking up stats on obscure places like Fayetteville, N.C., and focused instead on including interesting towns. For instance, I listed East St. Louis, although it has depopulated so badly, from 82,000 in 1950 to 18,000 in 2020, that it’s barely there anymore.

Keep in mind I’m measuring population within the official city limits. For instance, Detroit’s municipal population plummeted from 1,850,000 in 1950 to 639,000 in 2020. On the other hand, the overall Detroit metro area, including both the city and its suburbs, has added a million people over the same time period. But I’ve graphed only the population within the city limits. That gives us better insight into how a high black share tends to drive down population density in the long run.

But focusing on the population within the city limits also raises the question of what to do when the shape of the city changes, such as by annexing its suburbs.

Paradoxically, conservative Southern states tend to have more pro-big-city laws making it easier for the urban core municipality to imperialistically take over suburbs, even against their will. In contrast, more liberal Northern states seldom let their inner cities plunder their tax-rich suburbs through annexation.

Thus, ultraliberal Boston and San Francisco take up only a small fraction of their wealthy metro areas because Massachusetts and California won’t let them gobble up Wellesley and Marin County, while Houston and, lately, Charlotte have absorbed much of their hinterlands.

I excluded four cities (Louisville, Ky.; Columbus, Ohio; Memphis, Tenn.; and Macon, Ga.) that I could tell had aggressively added large numbers of people to their official rolls by annexation or merging the city government with the county government. For instance, the population of Memphis nominally fell only 3 percent in this century. But that’s because it annexed fifteen suburbs. Otherwise, 63 percent black Memphis would have notably declined in population.

But I’m sure I didn’t catch all the cities that artificially enlarged their domains. So, the different policies on annexations no doubt add noise to the graph above.

Somebody with more expertise than myself should look closely at the data table below and try to figure out why, say, stable Montgomery, Ala., is doing better than shrinking Birmingham, Ala. Is there some methodological reason involving annexations? Is it just because Montgomery is a state capital with white-collar jobs while Birmingham is an old steel town? Or did Montgomery’s city fathers really hit on some winning strategies, as they like to brag?

Even with all the randomness caused by political changes in boundaries, the general patterns are clear. It’s not that highly black cities are necessarily doomed to eventual desolation, but they do tend to be at risk.

How does the U.S. avoid more urban death spirals of the kind seen in Jackson? How do we make it more in the interest of nonblacks to help urban blacks by supplying needed taxes and competence?

The single most positive step toward encouraging other races to want to live in cities with lots of blacks would be for blacks to lower their murder rate, which is currently about an order of magnitude higher than the white rate, down toward the Latino rate, which is only a little more than double the white rate.

But instead, our leaders have been egging on black bad behavior. If elites don’t knock off their irresponsibility, we can look forward to two, three, many Jacksons.