A quick glance at RCP poll averages for Super Tuesday makes it clear that we need to start girding ourselves for the contemplation of a prospect truly terrifying”President McCain. Our friend Leon Hadar has already started starring into the abyss:

For those of us who opposed the Iraq War and W’s foreign policy”and for opponents of Big Government, in general”all of this [the coming McCain GOP nomination] is VERY BAD news.

Bush is basically a lazy person with little interest in global affairs and all his warmongering was all about winning elections, not about fighting wars. He really doesn”t like sitting late at night in the Situation Room “managing” a global crisis. He prefers to go to bed (to sleep).

But McCain LOVES all of that. Another Cuban-Missile-Crisis-like atmosphere in the White House where he could play the War President. It’s a form of Viagra for this mummy-like creature. It could keep him alive and kicking for eight more years during which the Warfare State will run amok, including the … reinstatement of the draft. Sometime in 2010 we”ll have no choice but to admit that we are really starting to miss W.”

We should be wary of any dailykos-like rants about “the Republicans are going to reinstate the draft and install fascism ahhh!” but I generally think that Hadar is raising a real possibility. As Justin pointed out last night in his live-blogging, McCain’s war-hero identity often leads him to conflate politics with military duty. His “I led for patriotism, not for profit” was, of course, a thinly disguised shot at Romney, Mr. multi-millionaire. But what is McCain actually saying here? I don”t know how useful McCain’s experience leading a military brigade would be in the White House”unless one imagines the president’s central role as dealing with soldiers in a series of war crises. (Moreover, McCain statement begs the question, would Romney be more qualified for the presidency if he had notprofited during his time in the non-military sector? Is McCain bringing into doubt the leadership of every person who’s been so slimy as to make money from a business transaction?)

Anyway, the point is that while Bush wanted us to fight terror by going shopping, McCain might try to revive that old 9/11 feeling through enlistment.

Hadar goes on:

“Finally, I do hope that Dr. Paul runs as a third-party candidate and makes it more likely that the Republicans lose, providing them with an opportunity to reinvent themselves.”

From what I”m hearing, a third-party bid is not very likely”Paul doesn”t have particularly good memories from his Libertarian candidacy in “88, and judging from his recent debate performances, his heart no longer seems to be in his current run.

This aside, Hadar thinks a Ron Paul third party would be positive only in that it would derail a likely McCain victory in November. In Hadar’s mind, the senator will win with Bush’s “04 strategy: using “foreign policy/national security” especially against the backdrop of a possible confrontation with Iran … and the alleged “success in Iraq”to bash Hillary and the Democrats as “appeasers” etc.”

While I think McCain would probably run like this, I”m not so sure it would work. I generally think the public is tired of the 9/11 paradigm. Whatever you want to say about Huckabee & Obama (I don”t have much of anything good to say about either), they”ve beaten the establishment’s erstwhile “inevitable” candidates by running outside the 9/11 box”no Kerry-esque “reporting for duty” here. Moreover, Romney has consistently finished second on “change” + “Washington is broken” rhetoric. The fact is that a McCainian GOP would probably lose hard in November with or without a Paul third-party run. Nevertheless, whether the establishment and base is really willing to “reinvent themselves” afterwards is doubtful”as what? led by whom?

Still, there’s a certain bleak fatalistic fun in contemplating the composition of a McCain admin:

As Hadar see’s it:

Vice-President: Rice or Huckabee or Lieberman.

Pentagon: Giuliani or Rice or Lieberman.

State: Robert Kagan.

AG: Giuliani.

CIA: Giuliani or Gary Schmitt.

Colonial Office: Niall Ferguson.

Treasury: Robert Zoellick.

Representative in Israel: Bibi Netanyahu

I”ll nominate Denis Miller as Minister of Culture and John Podhoretz as Poetic-Reference-to-1938 Laureate.

On Jan. 28, Christopher Hitchens went through the litany of Bill and Hillary’s long history of “race baiting” in Slate. The extent of Hitchens’s charges were that:

“¢ Clinton occasionally played golf at a Country Club with no black members.

“¢ Dick Morris once worked for Jesse Helms.

“¢ Clinton signed a death warrant for a black double murderer who had attempted suicide. (This makes Clinton far to the right on crime than the other governor from Hope )

This sordid history has culminated in Clinton’s comment that Barack Obama’s success in South Carolina was largely due to his carrying the black vote and that South Carolina’s democratic electorate is predominantly black. Clinton noted that Jesse Jackson also won South Carolina for the same demographic reasons.

Hitchens rhetorically asks, “Did Jackson come south having already got himself elected the senator from Illinois?” Well, of course, Jackson did not get himself elected to the Senate. His sole qualification for president was his experience as a race huckster and extortionist, but he still managed to carry 11 states almost solely due to his monopoly on the black vote. That Obama, the Senator who supposedly transcends race, didn”t do all that much better than Jackson proves Clinton’s point.

Hitchens also asked, “And, come to think of it, was Jackson so much to be despised and sneered at when he was needed as Clinton’s “confessor,” along with Billy Graham, during the squalor of impeachment?” Well, Clinton didn”t say anything bad about Jackson. He said, “Jackson ran a good campaign. And Obama ran a good campaign here.” So now “our first black president” is a racist fore uttering “Jesse Jackson” in an adjacent sentence about our next black president.

Hitchens contrasted the racist Clintons to Obama who has made “no sectarian appeal to any specific kind of voter.” But then he doesn”t have to. Now that he has proven his blackness, virtually all African American voters are behind Obama.

Unlike Jesse Jackson, Obama is not overtly offensive and talks in platitudes rather than with vitriol. Liberals, and many conservatives, now beam about how great it would be to have a “new face for America” and what a great a step forward it would be to have a black president. Even if Obama doesn”t use race as an issue, his success has been almost solely due to the fact that he’s black.

It would be easy to engage in schadenfreude now that Clinton’s great “Initiative on Race“ is catching up to him. Were it to stop with the Clintons, I”d be happy to watch them hoisted by their own petard, but it will not stop with them.

In one of his few moments of insight, Jonah Goldberg laid bare an implicit assumption surrounding Obama’s campaign: “Given recent events, it seems that if you’re not with the Obama program, you’re fair game for tarring as a crypto-racist.” We certainly got a taste of this when many in the chattering class whispered that Obama’s loss in New Hampshire was due to “racism” in the granite state. Goldberg asks, “If Obama becomes the Democratic nominee, imagine what hairballs will be coughed up at the Republicans.”

Many of Obama’s supporters hope that if he’s elected, it would prove how non-racist America is. Instead, it would prove how race can shield a candidate from any kind of serious criticism.

From one of my favorite liberal Democratic bloggers:

“The most pathetic thing about Barack Obama’s efforts to bow and scrape for AIPAC are that the AIPAC crowd has been suspicious of him from Day One and his pandering doesn’t change the fact that they don’t like him. Why not just accept that he’ll have to live without that small segment of the public and stand up for a more reasonable policy? Instead, he seems determined to pander in vain.”

Why the pathetic pandering? Just ask Wesley Clark.

At long last, we arrive at the end of the line, having examined first race and then nationalism. I’d like to thank once again all those who have taken part in these discussions, which have, for the most part, been quite civil, even in the midst of strong disagreements (with a few notable exceptions).

In this final part of my series, I’m again relying heavily on the work of John Lukacs, and I would refer the reader, in particular, to his Outgrowing Democracy: A History of the United States in the 20th Century (lately reissued as A New Republic), The End of the 20th Century (and the End of the Modern Age), and Democracy and Populism.

As I mentioned in the previous part, Pope John Paul II, in his last book, Memory and Identity, defined patriotism as “a love for everything to do with our native land: its history, its traditions, its language, its natural features. It is a love which extends also to the works of our compatriots and the fruits of their genius.” In this, he follows the word back to its Latin root: patria, the native land or, literally, fatherland. But a patria, by itself, has no human meaning, any more than, say, environment does. From a human standpoint, both terms imply some relationship to some group of men.

In the case of patria, that group, as the Holy Father goes on to show, is the nation, which etymologically descends from the Latin natio, meaning, most broadly, a group of people, but more specifically a tribe, a race, a nation—in other words, a people who are connected, both genetically and culturally, in a way that is a natural extension of the family. Indeed, John Paul writes:

“The term ‘nation’ designates a community based in a given territory [i.e., patria] and distinguished by its culture. Catholic social doctrine holds that the family and the nation are both natural societies, not the product of mere convention.”

Historically in English, both patria and natio have come together in patriotism, the love of a particular people in a particular place. Again, this is analogous to the human society of the family, which, throughout history, has not simply been defined genetically or culturally but with reference to the physical location of the family. Our modern, mobile American society throws us off here, because we think nothing of moving from state to state several times in our lives, nor do we particularly find it odd to sell our childhood home after we inherit it (assuming our parents haven’t sold it long ago). Our sense of belonging to a particular place—not only being a part of a particular place, but that place being a part of us—is extremely attenuated.

But the modern American experience is not normative—not only historically, but even today, among European-derived peoples. Europeans in Europe are much more rooted, and that close association with the land of their fathers—the patria terra, to return to the Latin—has a cultural (and, indeed, even a genetic) significance that has largely been lost here in the United States.

It’s no surprise, then, that patriotism, in modern American usage, has diverged from its historical definition and largely come to mean abstract adherence to some set of American “ideals”—for instance, the “proposition nation” or “credal nation” idea of the neocons, or the Jaffa-ite version of the “noble lie” of the Straussians. After all, how can patriotism retain its traditional meaning for people whose connection to the land on which they currently reside is at best momentary and accidental? It makes little sense to develop an attachment to a place (and the people who reside therein) when we’re only “passing through,” looking forward to our next move, “onward and upward,” as we chase the “American dream.”

The result, in the United States, has been the separation of those two terms that should be inextricably linked—natio and patria—and the destruction of patriotism, as traditionally understood. But because natio and patria are linked, when our relationship to the latter is attenuated, the former becomes more abstract—an ideological construct, rather than a lived reality.

The answer is not to throw up our hands and declare ourselves “rootless cosmopolitans,” as some who have actually begun to see the problem have done, nor to think that an abstract nationalism (either the “proposition nation” or some defining away of our differences until “American” means nothing more than “of the white race, residing within the borders of the current United States”) will solve our problem. Instead, we need to return to life as our ancestors lived it, and as most Europeans today still do: in one place, among our people, through many generations.

In other words, the answer to the loss of traditional patriotism is a revival of patriotism. That may seem obvious, but the opposition to this solution runs deep, and not only among those who hate the culture and civilization of European man, but even among many of those who claim to be interested in upholding it. Standing our ground—literally—is quite hard, and when the opportunity to move on presents itself, we’re often only too happy to take it.

It’s not always possible to remain where you were planted (as I, sadly, know), but moving out of necessity is different from moving out of choice, and the proper response to the former is to begin the long and arduous process of putting down new roots. In that way, through long and close association with a particular people in a particular place, we can begin to recover something of the life that our ancestors lived—and to forge, as they did, a civilization worth preserving.

(As my regularly scheduled posting here on Taki’s Top Drawer comes to an end, I’d like to express my deep honor and pleasure at having had the opportunity to be part of this endeavor over the last year. And I’d like to thank those who made this possible: former editor F.J. Sarto and, of course, Taki Theodoracopulos himself. For those of you have despised what I have written, I’m afraid you’re still stuck with me: the new editor, Richard Spencer, has asked me to continue to provide the occasional blog post, as well as more frequent longer pieces. For those of you, on the other hand, who have liked what I’ve written, you can find more at ChroniclesMagazine.org, where I’ll likely be posting more often now, and the Chicago Daily Observer, among other places.)

Although I was pleasantly surprised to learn that Jonah praised my scholarship on NRO (Thursday, January 24, http:/liberalism.nationalreview. com/post/?) and that he considers me a paleo “who knows a lot about a lot,” there was one part of his message that troubles me. Jonah is apparently upset that The American Conservative, a magazine for which I have written, did not select me to review his book. It seems that Jonah was interested in having my views appear in that particular paleoconservative publication. And I too might have been pleased to review Jonah’s book there, although I couldn”t imagine that I would have found more positive things to say about his research in that venue than I reported on this website. Although Jonah claims that he “came to a newfound respect for some of my writings,” as he worked on his book, the evidence of my influence on the final product is at most sporadically apparent. For example, Jonah makes critical distinctions between Italian fascism and German National Socialism but then turns around and uses the two interchangeably to bash Democratic politicians. But, even more to the point, why should Scott McConnell and Kara Hopkins, who manage TAC, feel obligated to give me an assignment so that Jonah should be able to see my comments at their expense? Why couldn”t Jonah, who already has his own thriving website and who is connected to a magazine that supposedly has subscribers coming out of their ears, allow me to review his book for NRO or else in National Review magazine? Richard Spencer would certainly allow Jonah to have his say on this website and besides, would probably pay him for his contribution. Why can”t Jonah be equally generous?

Gentle readers, you know the answer. It is that Jonah’s bosses are leftist totalitarians while those on our website are willing to debate with people on the left as well as on the right. We are the liberals in the true sense of that term, while Jonah’s sponsors and control-people have about as much tolerance for anyone or anything standing on their right as John Zmirak does for the American Nazi Party. That is why FOXNEWS and NR, together with the rest of the neocon empire, showcase debates with leftists but would NEVER allow those who are even a smidgeon to their right to appear in their closed forums. I would no more expect to write for a publication to which Jonah is tied, no matter what he may say about my scholarly credentials, than I would expect to be asked to contribute to the Nation. An adjunct of the neocon empire, FOXNEWS, is constantly inviting the Nation’s editors on to its program. Bans are only applied against the Old Right. That is one of the points of my widely but predictably ignored recent monograph on making sense of the conservative movement. That movement is open to the left but is hermetically sealed off to critics farther on the right. Presumably that ban also extends to geriatric intellectual historians like me, for whose work Jonah professes respect

On January 28, someone on the Permanent Things website referred to my evaluation of Jonah’s work as “one more” invective against the neocons. For anyone who would care to notice, my critical comments were not directed against any such target. I was calling attention to what movement conservatives have come to treat as high learning. This judgment seems relevant in view of the statement that I”ve encountered in the national press since the mid-1980s, that the neoconservatives raised the intellectual horizons of the American Right. That assertion is patently false. What I have seen is exactly the opposite, and especially since the neocons began to marginalize thinkers associated with the Old Right and to impose ideological conformity on their hired journalists.

There were nuggets of truth concealed in Jonah’s work, which were never developed because he did not do enough research and because he felt constrained to provide partisan Republican propaganda. Even for someone like Jonah, who can turn phrases extremely well and who is obviously a lot smarter than most of his colleagues, it is impossible to go very far as a serious scholar because of the professional pressure to manufacture movement conservative propaganda. Jonah may be among the best of the journalists whom National Review can presently offer. But that might not be particularly high praise. If the movement had not expelled an entire generation of distinguished Old Right scholars, the discourse on the establishment right would not only look less leftist. It would also operate at a much higher level.

While none of my blood is (sadly) Italian, my arrival in Rome was the closest experience to a homecoming I think I shall ever have. I expect that feelings will stir as I visit the island, Unije, from which my grandfather sailed for NYC in 1916″and again at the tomb of my ancestral sovereigns in Vienna. But not even the hallowed ghosts of the most benevolent secular government ever to reign over Christian souls evoke the same devotion as the actual seat of the Vicars of Christ, which I have been privileged to visit for this year’s seasons of Carnival, Lent, and Easter. I am staying a few hundred feet from the Janiculum wall”which the Latin inscription informs me was restored in 1869 by the Blessed Pius IX, the last pope to govern Rome. One must-see spot on my itinerary is the Porta Pia, which the anticlerical armies of Garibaldi breached with dynamite, and Pio Nono ordered the Swiss Guard and the Papal Zouaves to lay down their arms.

I’ve already been privileged to visit some historic sites, accompanying Thomas More College students on tours led by my learned colleague Dr. Paul Connell. We’ve explored the tangled, dusty streets of Trastevere”the Greenwich Village of Rome, now sadly as gentrified as Bleecker Street”in search of Rome’s most historic churches. The loveliest so far has been Santa Maria in Trastevere, one of the oldest Christian sites in Rome. The historical record tells that ground on this site began to exude a precious oil some 30 years before the birth of Christ”and that local Jews (who made up much of the population in ancient Trastevere) took this as a sign that the Messiah was nigh. Enough of them accepted the good news St. Peter brought to Rome that a Christian community sprang up around the site; the inscriptions from their tombs and catacombs, rudely inscribed in Latin and Greek, are plastered into the facade of the present church, a structure of medieval origin that is ornate with Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo art. Best of all, its artworks are intertwined with the theme of oil—replete with virgins wise and foolish, all holding lamps.

The most significant spot in Trastevere, and perhaps in Rome, for those who care about the civilization of the West is a tiny chapel that dates from the 6th or 7th century called San Benedetto in Piscinula. Inside this badly battered, much restored little church is a crawlspace not much bigger than a coffin. It was in this monastic cell that St. Benedict lived during his time in Rome, before he removed to Subiaco, where he would compose the Rule of his religious order. Wiser men than I, such as the philosopher Alasdair Macintyre, have said that the only hope of restoration in the West will come from men like Benedict. It was monks of Benedict’s order who replanted the vines and restored the agricultural basis for life in a Europe rent by invasions of barbarian and Arab alike. One of the many inventions of the Benedictines was the liquor which bears their name. I wrote last year of Benedictine(s): “As the drink combines the leaves and blooms of field and fen to infuse a spirit, so St. Benedict yoked regular work and prayer to help men fuse with the Spirit. While the monks of the East might scorn and scourge the flesh, Benedict sought only to discipline it, to prune its passions and point it toward the Light. Monks of Benedict’s order weren”t known for burning pagan books”but patiently recopying them, in the confidence that the traces of wisdom they contained could nurture the growing body of Christendom.”

If I were to try to locate the Benedicts in Rome today, I’d have to leave Trastevere and head northeast, to another battered hole-in-the-wall parish called S. Gregorio dei Muratori. This church is served by the priests of the Fraternity of St. Peter”clerics who helped keep alive in the face of popular scorn and bureaucratic opposition the Church’s ancient Roman liturgy, which was cast off like an aging wife by an imprudent Pope Paul VI in 1970. It took an outright rebellion by the great African missionary Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre to save the ancient western rite from the memory hole. In 1988, when Pope John Paul II offered an olive branch to Lefebvre and his priests, it was rejected”except for a small group of priests who couldn’t endorse Lefebvre’s decision to ordain bishops without papal permission. These priests formed the Fraternity of St. Peter, and they accepted the deal which John Paul (at the urging of then-cardinal Ratzinger) had offered Lefebvre. It wasn’t particularly sweet”especially since few bishops around the world wanted much to do with priests they regarded as right-wing cranks. Meanwhile, the FSSP priests found themselves denounced as “traitors” and “dupes” by traditionalists who refused to make a deal with a Vatican they considered hopelessly compromised. Several of my friends pursued studies with the FSSP, whose program for anglophone seminarians was poorly organized at the time. Indeed, when the first crowd of hopeful young Americans arrived at Wigratzbad in (I believe) 1990, all the theology courses were either in German or French”but there were no language courses offered in either tongue. Recriminations over the split with Archbishop Lefebvre divided the seminarians into factions, and the food was awful even for Germany. As one would-be priest told me at the time: “All we have is meat and starch. I’ve been eating knudel for weeks. Every single person here has gained 20 pounds and is terminally constipated. No wonder we’re not getting along.”

It took some years to iron out such wrinkles. Now the Fraternity has a thriving English-language seminary in Denton, Nebraska, and serves around the world. What is more, its dogged insistence on retaining the reverent liturgy which (with few changes over the centuries) helped form saints from Benedict up through Padre Pio was vindicated in September, 2007 by Pope Benedict’s motu proprio Summorum Pontificum“which restored the old (“extraordinary”) form of the Roman rite to equal status with the new one crafted in 1970 (by an ecumenical committee). Interest in the old rite is spreading among the young, and youthful priests are taking lessons in Latin and proper rubrics. The bewildering scandal created in the 1970s by (let’s take these words one at a time) a Vatican… punishing… priests…for cleaving… to ancient… prayers seems likely to end”as the good Pope Benedict pursues a peace treaty with the still unreconciled traditionalists of the Society of St. Pius X.

This matters to more than Catholics. The Church is a bellwether of the fortunes of everything important to conservatives”family life, localism, education, you name it and the Church is crucial to its survival or disappearance. A wit in the 1920s once reassured the world that Bolshevism could not spread so long as it was restrained by “the German General Staff, the British House of Lords, the Academie Française, and the Holy See.” There isn’t much fight left in 1), 2) and 3), and since 1970 it has been unclear on which side much of the Church was playing. While the Church of Christ does not exist to save Western or any other civilization, such conservation is typically a happy side effect. It was Gregory the Great who saved the city of Rome from ruin in the Dark Ages and St. Benedict who passed along the light of learning all over Europe. Just now, I believe it is the priest of the FSSP who are handing on “the permanent things.” That’s why I was happy to join them this Sunday past for Solemn Mass at their hole in the wall. Just as the vast vineyards, libraries, and universities of the West crawled one day out of that cell in Trastevere, so the flame that these good priests have been tending at San Gregorio has relit every lamp in the Vatican.

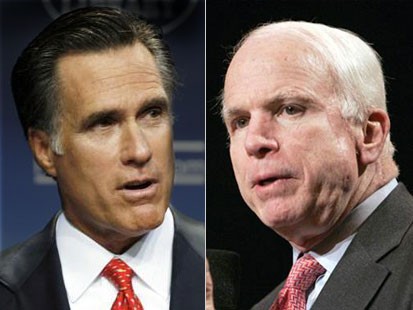

The opening shot on CNN saw Ron Paul getting friendly with Mitt Romney and John McCain, who gave his principal ideological opponent a patronizing pat on the back.

Are Americans better off now than they were 8 years ago?

Mitt Romney says he’s not running on President Bush’s record. “Washington is broken.” Broken—by whom?

Mad John McCain rambles on and on—starting off by saying, “yes, we are better off”—and then going into a litany of our economic woes. Alzheimer’s up close and ugly.

Huckabee: Attacks Congress: let’s not blame the President. Housing is on everyone’s mind: people’s homes are worth less. The Huckster will do something about it. What, exactly, is that? “Serious leadership”—to do what? It’s not clear.

Ron Paul: No we aren’t better off. We’re victims of fiscal policy, monetary policy, and a foreign policy that is bankrupting America, and impoverishing us all. Paul delivers a comprehensive and clear explanation of why we’re in trouble, and how to get out. Home run—and a study in contrast, especially with the stumbling bumbling McCain.

In response to a question about his attacks on McCain as not a real conservative, Mitt Romney is beating up on McCain on global warming, and the endorsement by the New York Times.

McCain gets a really ugly look on his face and rears up, braying that his hometown newspapers are endorsing him, while the Boston Herald is not endorsing Romney. There is some truth in what he says—Romney is a moderate, what we used to call a Rockefeller Republican—but the look on Mad John’s face is just plain scary. This is the guy whose finger we want on the nuclear trigger? I think not.

The Huckster is asked about Rush Limbaugh’s remarks to the effect that his nomination would mean the destruction of the GOP. He’s personally appealing, and very direct: authenticity shows, and it’s very appealing—as are his California ads demanding the abolition of the IRS. He’s saying he wants in on the discussion about conservatism that was being monopolized by what was and is turning into the Romney-McCain sweepstakes. The interviewers—one of whom is from The Politico—are openly shaping the debate. The exclusion of Paul is embarrassing—for them.

How come every time I hear Romney’s voice he’s talking about fees and why he had to raise them? Not good.

And that woman from the LA Times? The Nurse Diesel of American politics.

All but Paul are babbling about”energy independence”—but what can this mean? One can easily see a progression of this idea that underscores the underlying absurdity of the original: after all, why not “food independence,” and “metallic independence”—and, ultimately, “intellectual independence” (hey, it even sounds good!). Only made-in-America medical inoovations ought to be allowed! Oil exists in certain areas of the world: we want to buy it, they want to sell it. What’s the problem?

Ron Paul was finally asked a question, he started to answer, and was rudely cut off by that aging CNN twink[Anderson Cooper]—who promised he’d get a chance to speak in “two minutes.” Yeah, like hell.

The Huckster wants a public works program to stimulate the economy. Romney says its a good idea but not practical. Ron Paul hits another home run—okay, the twink did keep his promise—by clearly stating that what we need is a freeing up of the economy and a foreign policy that doesn’t cost us trillions. “We’re going around the world blowing up bridges and our own bridges are falling down.” Go Ron go!

McCain taking his cues from the Huckster: we need to “punish some people on Wall Street” and bail out the subprime crowd. The hypocrite then turns to Ron Paul and says “The one place where I agree with Ron Paul is that we have to stop the spending.” Yeah, end the war, John—that’ll save us billions—your “hundred year” occupation of Iraq will cost us trillions.

Why didn’t you support tax cuts? McCain is defensive, and squirming. Romney jumps on him: McCain is visibly fuming.

We have to “grow” the military and shrink the domestic spending—that’s what Romney wants. A platform that has as much appeal as Mormonism outside of Utah.

The Huckster on immigration: we need a fence to keep out illegals. It’s not to be cruel. It’s because we don’t want people running when they see a police car. (“Don’t tase me, Bro!”). Romney taking after the “Z” visa arrangement, which was de facto amnesty for illegal immigrants, which is really an attack on McCain. Great little lecture, which garners applause. Score one for Mitt. This issue could sink McCain.

Now McCain is getting accused of downplaying the immigration issue, because he voted for and campaigned for the “Z”-visa proposal. Oh, it isn’t pretty! And yet it is beautiful.

Tamper-proof biometric documents? That’s McCain’s “solution” to the immigration question, which is suppose to assure us that he wants to “secure the borders.” Question: Will every American have to carry this “biometric” documents?

would you have appointed Justice Sandra Day O’Connor is the next dumb-ass question.

he Huckster pontificates on abortion, not very convincingly, after deftly evading the question.

I wouldn’t have appointed a Sandra Day O’Connor, says Ron Paul, declaring that he’d prefer someone with a stricter interpretaion of the Constitution. Then he is cut off by the twink.

Peggy Noonan is cited by the twink on how Bush “destroyed the Republican party”—doesn’t blame Bush. Hails Bush, the war, and engenders the most sustained burst of applause. Getting out is more important than “winning” to the Democrats. Yeah, Mitt, the country isn’t buying it. Let’s all the pro-war conservatives get together on this.

Mitt is asked if McCain’s “charge” that he supports a “timetable” for withdrawal from Iraq. Who me? He throws up his hands: it’s a lie! A heinous lie! I will not pull our troops out in Iraq—no safe havens for Al Qaeda, Hezbollah, “or anyone else.” Now he’s whining that the whole thing is a “dirty trick.” Lusty applause for that pathetic wimp.

McCain is snarling. He repeats the “lie,” while characterizing himself as “out there on the front lines with my friends,” and claims authorship of the “surge.” Now they’re spluttering at each other. A lot of macho posturing. McCain has used the word “I” dozens of times in the past few minutes.

McCain has said that he envisions a US occupation of Iraq that lasts “one hundred years.” No one mentions this.

The twink is allied with McCain, and is now grilling Romney why he didn’t speak out in favor of the “surge” while he was a governor. Screw you, twink. That ‘s what he ought to say, but he’s dancing to the party line. The whole display is a disgusting warmongering competition that will kill the GOP at the polls in November—hopefully.

Someone is asking Ron Paul the “hundred year” question I anticipated. Ron is hitting another home run. We can’t afford an empire—we’re in bankruptcy. It’s a sustained peroration against the idea of imperialism, which nevertheless manages to stay rooted in the specifics of the case—the lies that led us into the quagmire—and gets a big round of applause.

Only casualties matter: we can be in there 100 years, he mentions Korea: he attacks Rumsfeld, hails Petraeus, “come home with honor”—we’re “the world’s superpower and we hae to be a lot of places.” Tepid applause.

Huckabee is asked about Bush’s famous comment that he looked into Putin’s eyes and saw a kindred soul: Huckster evades the question, and segues clumsily into a speech about how we need to have “enough troop strength.”

Romney is asked the same question: Russia is headed down the road to authoritarianism, launches into wild accusations—“unexplained murders”—Wow! Russia is using oil to “take over the world.” China is “communism and a wild capitalism”—and they are also trying to take over the world. Then there’s Al Qaeda. And then there’s us, the good guys. So we need to subdue them all—he’s trying to out McCain McCain.

What is this “radical Islamic extremism”? Is there such a thing as moderate Islamic extremism? Get off of it, guys. God, McCain is such a rancorous blaggart: “unshakeable,” “patriot,”—an ego as big as the solar system.

Now Romney is defending the idea of being a businessman, against McCain’s attack on him as someone who was motivated by “profit” rather than “duty.” He’s hitting McCain pretty hard, defending the Republican small business base against McCain super-militaristic concept of the ideal human being.

The twink is taking McCain’s side, again, asking Romney why he’s more qualified than

Paul is giving them a lecture about why the President is not a dictator, and the commander is chief is not the commander in chief of the economy. A basic lesson in basic libertarian principles—and he’s bringing in foreign policy, as always! He always brings it back to essentials, tying in the Fedeal Reserve’s inflationary policies and the way inflationary monetary policy finances wars that we shouldn’t be fighting.

I love the look on the faces of Romney and especially McCain. Another home run for Ron.

The Huckster rambles about nothing—a governor can do anything, even lead the free world. He’s babbling on about “the people at the bottom.” The Huey Long of the GOP.

A question asked of all: why would Ronald Reagan endorse you?

Romney is trying to convince us that he’s the “independent conservative” and “outsider” who will come to Washington and effect a revolution, just like Reagan. Not very convincing.

McCain goes negative, attacking Romney albeit not by name, as a flip-flopper.

Ron Paul: I supported Reagan in 1976 , one of four congressmen to do so: he reminds the audience that Reagan campaigned for him a few years later. He then relates a very effective anecdote about Reagan, recalling that Reagan once told him that he agreed with Paul’s views on the gold standard. “No great nation that goes off the gold standard stays great,” Reagan told him. Paul then goes into a clear, concise and very effective riff on how the decline of the value of the dollar punishes us all, and must e stopped.

Paul clearly won this debate—and while operationg at the distinct disadvantaged of being systematically ignored. This will win him votes, notice, and yet more contributions, as the Huckster runs out of steam and Romney stumbles.

Postscript: Here’s a transcript of the proceedings, so you can check my spin against what really happened.

Matt Yglesias has it right:

“Whatever else happens in 2008, one thing that’s certain is that Rudy Giuliani won’t be elected president. That’s something I’m thankful for. And, based on the results, I think it’s something that virtually everyone in America can be thankful for—something that can unite Americans across the cultural divide. From Red America to Blue America, everywhere but the Commentary office and the foreign policy wing of the American Enterprise Institute, we stand proud tonight as a nation that refuses to be governed by Rudy.”

One wonders what John Zmirak will dream of as jet engines humming incandescently waft him through the Atlantic night on his first pilgrimage to Rome. In the aftermath of jet liners truncating Manhattan’s image of itself, many neoconservatives are rightfully obsessed with the consequences of modern weapons falling into the hands of medieval-minded Islamic fanatics. It is a nightmare that troubles palaeoconservatives and mere Realists as well, but few in any of their camps seem to have considered a worse contingency”Western civilization dropping its guns and abandoning its massive lead in the inter-civilizational arms race.

That’s what happened to Islam some seven centuries ago, when the Arab answer to the Theocons of today took it upon themselves to tar the West Asian technological renaissance with the attainder of godless materialism. Their learned synods barred intellectual investment in science, lest it distract good Muslims from submission to the will of Allah, in Whom the fate of nations rests. Latter day fundamentalists do not like post-Biblical (or post-Koranic, or post-Vedic) history any more than they. If they did, more might use their God given wits to figure out that fears of Islamic terrorism were even more acute in medieval times.

Fanatics were fanatic as ever and the Islamic world more advanced in military technology than Christendom in everything from metallurgy to navigation. Until the Damascus steel and Greek fire armed Saracens were suppressed, not by Byzantines or Crusaders, but the Mongols, they sanctioned al-Qaeda’s distant exemplars, those echt terrorists, the Assassins, who, when not slitting Templar throats, exported jihad to the Franks own turf, slaying royals in France as well as monarchs of the Crusader kingdoms of the Levant.

The Arabs enjoyed centuries of military ascendancy not just because the were fired by their faith, or able to acquire re-enforcements among the conquered- the familiar particulars of Islamic sociology set forth by Ibn Khaldun, but because they were all the while in closer proximity to both the roots of Hellenistic technology, and the greatest source of military innovation of the age.

Tang China was vastly more advanced in its mastery of materials and chemistry, leading the West by centuries in areas ranging from gunpowder and iron casting to porcelain and pharmaceuticals. Until well after Marco Polo, Europe was clueless to this, because, as with the anti-proliferation regime of today, all contact with the Orient was filtered through trade routes utterly controlled by the Caliphate and its Turkic and Persian offspring. Hence, Islam’s centuries of unchallenged military dominance on land. Yet after throwing the Crusaders out of most of their conquered lands in the 13th century, Islam faltered”it never reversed the re-conquest of Spain, and lost its foothold in Italy. What brought Islam’s technology-led Second Millennium advance to a halt?

In a word, religious fundamentalism. Once Islamic theologians in Cairo decided that Koranic exegesis was a done deal, speculation in secular areas became intellectually suspect. No more disputation on the meaning of Greek philosophy, dialog with Jewish, Zoroastrian, Coptic, or Nestorian divines, or pointing to experiments and observations to challenge the Final Word of Allah, as contained in the Al-Azar approved concordance to the Koran and the hadith of God’s Messenger.

The result was stasis, and the strategic timing could not have been worse, for Europe’s long banked intellectual fires were reigniting just as the Fatamid’s were being doused. The Ottomans and the Savafids would experience the Renaissance by contact and osmosis, but the vast Islamic hinterland, from the Mahgreb to Indonesia, would slumber on, clueless through the centuries, until The Age Of Exploration swept over it and that of Empire began.

By then it was too late”allow a one-century deep technology gap to develop, and it may take four to regain the lost ground. That’s why, in 1898, an embedded reporter in the war against Islamic terror in the Sudan could thank more than his God for his survival in a battle fought at odds of five to one, as he observed:

“How dreadful are the curses Mohammedanism lays on its votaries … No stronger retrograde force exists in the world. Were it not that Christianity is sheltered in the strong arms of science”the science against which it had vainly struggled”the civilization of modern Europe might fall as did that of Rome.”

Young Winston Churchill’s precocious grasp of technology’s role in the Battle of Omduran explains his willingness for decades after to risk lives and treasure to develop such ungodly manifestations of materialism as alloy steel armor, shaped charge explosives, radar and cybernetics. Had he stopped more often to say his prayers, he would have materially altered the course of history. One possible outcome being Hitler and Stalin gladly providing a present age too deficient in classical liberalism to accommodate any Conservatism we know of today.

It is in the light of this mere history that the mind is repelled when clicking the link on the words “Materialists of the Right” in Mr. Zmirak’s recent article up pops a man of small mind ranting of the ghosts in his gene pool like a dervish drunk on cheap Djinn. If this be materialism, Madonna must be the second coming of Wittgenstein, and the way clear for Jonah Goldberg to write a sequel to Liberal Fascism explaining how, matter being the root of all evil, al-Qaeda draws its inspiration from the cantos of Ezra Pound.

Lord knows, a lot was the matter with him.

As we continue this series on race, nationalism, and patriotism, I’d like to note that the discussion on Part I: Race has been more subdued and thoughtful than similar discussions, and I’d like to thank those who have taken part in it.

In this second part, I rely quite heavily on the writings of the Hungarian-American (and Catholic) historian John Lukacs, though, for the sake of space, I’m not going to quote him. I’ve mentioned him, however, in case the reader would like to examine nationalism in greater detail, since I have only the space and time barely to touch on this issue.

In any discussion of nationalism, the first thing we need to do is to define our terms. Many people use the terms nationalism, patriotism, and even national identity interchangeably. For the purposes of this discussion, I will not. National identity is the consciousness of our close relationship to others who share a common language, culture, genetic endowment, and homeland, among other things. It is a constituent part of both nationalism and patriotism.

Against those who believe that national identity is a modern construct that has no basis in reality, Pope John Paul II, in his last book, Memory and Identity, points out that “Catholic social doctrine holds that the family and the nation are both natural societies, not the product of mere convention.” The mention of doctrine is important here: The Catholic libertarian, for example, who adamantly rejects the very notion of the nation in favor of a modern liberal understanding of universal humanity, is (as the Holy Father makes clear) dissenting from doctrine.

Patriotism, writes Pope John Paul II in the same book, “is a love for everything to do with our native land: its history, its traditions, its language, its natural features. It is a love which extends also to the works of our compatriots and the fruits of their genius.” Or, to sum it up as I have in other discussions of the works of John Lukacs, patriotism is the love of a particular people in a particular place (and the place is just as important as the people).

Nationalism, on the other hand, is, in its pure form, something different. As Pope John Paul II writes, “[N]ationalism involves recognizing and pursuing the good of one’s own nation alone, without regard for the rights of others.” It is insular, and not in a good sense; it not only assumes the superiority of one’s nation over the nations of others (which is not necessarily a bad thing in itself), but it refuses to acknowledge or understand that others might regard their nation in the same way. It can also (and often does) separate itself from a particular place, its native land. The nationalist can be rootless; the patriot cannot.

That is why nationalism tends to be expansive, imperialistic, while patriotism does not. Obviously, in the real world, these categories are rarely found unmixed. Even the most rabid nationalist likely has some patriotic feelings; while the most ardent patriot may find himself slipping into nationalism. What’s most important to understand is that these are poles of experience.

When modern liberals (and, on the right, their libertarian confrères) denounce the nation-state, most of what they object to—imperialistic wars, for instance—is nationalism. But not all, and this is where things can get a bit confusing. Within any particular nation, the opposite of the nationalist should be the patriot. But today, we often see nationalism as the primary bulwark against internationalism, and it’s certainly true that, against those forces and organizations that would destroy national sovereignty, the patriot might well ally himself with the nationalist. Remember, national identity is a constituent part of both patriotism and nationalism, but (obviously) it is not a part of internationalism.

On the other hand, in practical terms, nationalist movements can, paradoxically, advance the cause of internationalism. Montenegro’s secession from Serbia is a case in point. It was motivated by Montenegrin nationalism, and opposed by Montenegrin patriots such as the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitan of Montenegro, Amphilochius. In the end, the nationalists won, by prostrating themselves before the European Union. Today, Montenegro is, for all intents and purposes, a satrapy of the European Union, whose power has been increased through a successful nationalist movement.

Within the context of the United States, with its massive internal migrations, increasing loss of national sovereignty, and the influx of huge numbers of immigrants who not only cannot (by definition) be American patriots (at least when they arrive) but are also frequently Mexican nationalists, the issue can become even more ambiguous. It is possible, for instance, that the road to a revival of patriotism in America runs through American nationalism. (John Lukacs, who has criticized what he regards as the nationalist tendencies in Pat Buchanan, also clearly admires Mr. Buchanan.)

It’s certainly true that many who consider themselves American nationalists are more patriotic than nationalistic, but it’s equally true that many who would eschew the term nationalist—such as the neoconservatives who run our government—are the most rabid nationalists in the United States today, in the sense that John Lukacs and Pope John Paul II use the word. The task for true patriots today is to encourage the patriotic impulse in the first group, while adamantly opposing the nationalism of the second.